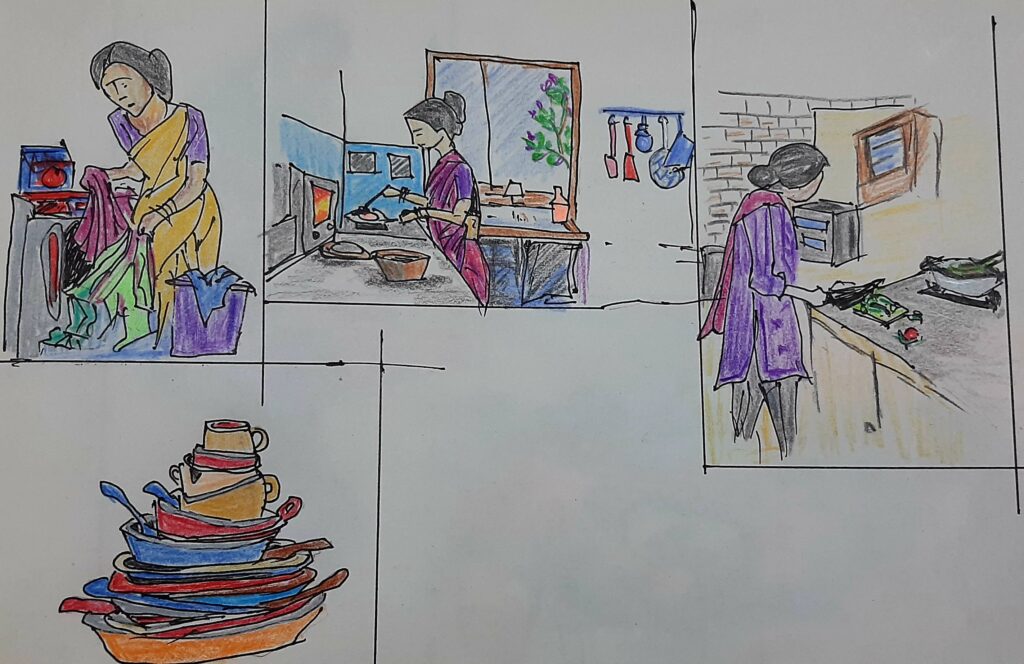

Domestic workers in India are demanding justice and respect. Anita Kapoor, a founding member of the Shahri Mahila Kaamgar Union (SMKU – an unregistered union working with domestic workers in the Delhi-NCR region), shares the experiences and demands of domestic workers through their own words for International Domestic Workers’ Day.

We, the domestic workers, are on the margins of society due to the utter neglect of society and the Government. Our situation was further worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic and consequent lockdowns. We were swamped by death, illness, hunger and helplessness. We left our livelihoods in the cities. We walked thousands of kilometres to return to our villages on hungry stomachs. Where was the government then?

Domestic workers were accused of being carriers of the virus. Our employers began to look at us with eyes of hatred. Where was the government then?

In the name of the pandemic, we, women domestic workers, became unemployed and injustice was inflicted upon us. Where was the government then?

Who gave the police an open license to harass us on the streets when we were struggling with these worries?

The Covid-19 lockdowns ruined our lives

We worked hard to earn a livelihood and a life of dignity, but the pandemic pushed us to a situation of utter helplessness. Many domestic workers lost their livelihoods and income and had no idea when they would be reinstated. Not only did they not have monthly incomes, but they also lacked rations and health services due both to the lockdowns and to poorly designed support measures. This was the time that domestic workers and their households needed support the most, and yet we found that our appointed representatives did not extend their hands in support.

The methods used to deal with the pandemic perpetrated caste violence, economic, exploitation and religious atrocities. The education of children was wrecked. Bodies were flowing in rivers. There were long queues at cremation grounds and graveyards. There were oxygen shortages in hospitals. Large companies were given debt relief. The economy was in tatters. but crowds for elections were exempted. People were permitted to join the Kumbh Mela. The courts and systems of justice were closed. Instead of the parliamentarians being open to hearing people’s issues, parliamentary sessions were cut short and anti-people farmers’ laws and labour laws were passed. The regime was absent.

Our employers exploited our vulnerability during the Covid-19 pandemic to decrease wages and convert our working status to full-time live-in workers. For us, it was not the Covid-19 virus that was the problem, but the violence inflicted on us by our employers – the decrease in our wages, the non-stop 24-hour workday, the hateful looks, the cruelty – these were our real struggles.

These have been lasting effects on domestic workers, undoing all the progress we made in the past decades. Previously, we had the power to voice our demands, even if it was only for four days of holiday and a 500 INR bonus during festivals. But the pandemic robbed us of even that limited bargaining power and the capacity to organise.

The issue of unemployment is rife in our sector. The demonetisation of the Indian currency in 2016, followed by the pandemic, has caused us to sink under the weight of indebtedness and economic burdens. Our husbands and even our children do not have secure employment. We feel the burden of running our households. As a result, we are not always in good physical or mental health.

Our demands

Given the situation and challenges faced by domestic workers, we have several demands for the Government. We demand appropriate wages, a day’s leave in a week, fixed hours of work in a day and the assurance of provident fund, pension, workers’ social security, etc. We demand a regulator for the employers so that the many atrocities and forms of violence against workers stop.

It is important for domestic workers to speak together about what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and about the issues that we continue to face to this day. It is important for us to document and investigate these issues and demand accountability from the government. In this work, we all have a collective responsibility. Across India, various organisations are conducting public hearings calling for accountability. Allied domestic workers’ unions must also join hands with the National Platform for Domestic Workers to put pressure on the government to concede our demands. We must investigate government policies by setting up public inquiry committees in different places. This is our fundamental constitutional duty. It is our responsibility to undertake. All the people of this country have to join in these efforts.

The voices of domestic workers proclaim:

“COVID is a symbol of the violence and atrocities against domestic workers”

“Respect, dignity, love and rest – this is our demand as workers”

“Pay us the right price for our work- this is our slogan as workers”

“Let us gain our rights as workers – this our demand as domestic workers”

“Domestic work is work! Recognise domestic workers as workers!”

“Fix minimum wages for domestic workers now!”

“Fix our hours of work now!”

“We are workers, not slaves!”

“On the issues of livelihoods, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“On the issue of domestic workers, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“We will ensure accountability for what happened with us!”

This blog was produced in collaboration with Countering Backlash partner, Gender at Work Consulting – India, and originally written in Hindi (translation provided by Sudarsana Kundu and Shraddha Chigateri).