The queer community in India has been continuously fighting for social equality over the last few decades, given the colonial era laws like Section 377 that criminalised same sex relationships and the Criminal Tribes law that outlawed entire transgender community. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and asexual (LGBTQ+) groups have struggled in police stations, courtrooms and on the streets to access their rights as equal citizens of the country, given the widespread stigma and discrimination faced daily, not only within homes and neighbourhoods, but within private and state institutions.

The long-standing fight for equal rights

After many challenges and setbacks, the LGBTQ+ community was able to gain a few significant victories. These include landmark cases such as National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) v. Union of India (2014) where the Court held that the state must recognize persons who fall outside the male-female binary as ‘third gender persons’ and that they are entitled to all constitutionally guaranteed rights. This was followed by Justice KS Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) in which the court held that the Constitution protects the right of a person to exercise their sexual orientation. The most recent judgement was Navtej Singh Johar and Ors v. Union of India (2018) in which the court held that Section 377 is unconstitutional to the extent that it criminalizes consensual sexual activities by the LGBTQ+ community. In 2019, the government of India enacted the Transgender Persons (protection of Rights) Act that recognized the right of transgender persons to have a self-perceived gender identity, prohibited discrimination and upheld their rights to residence, healthcare, education and employment.

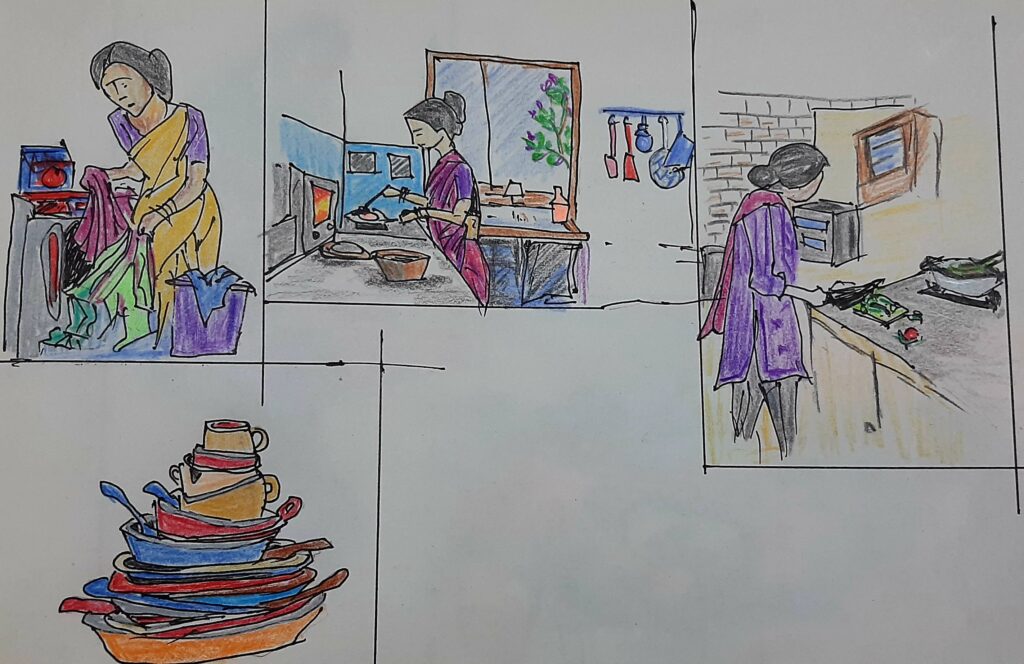

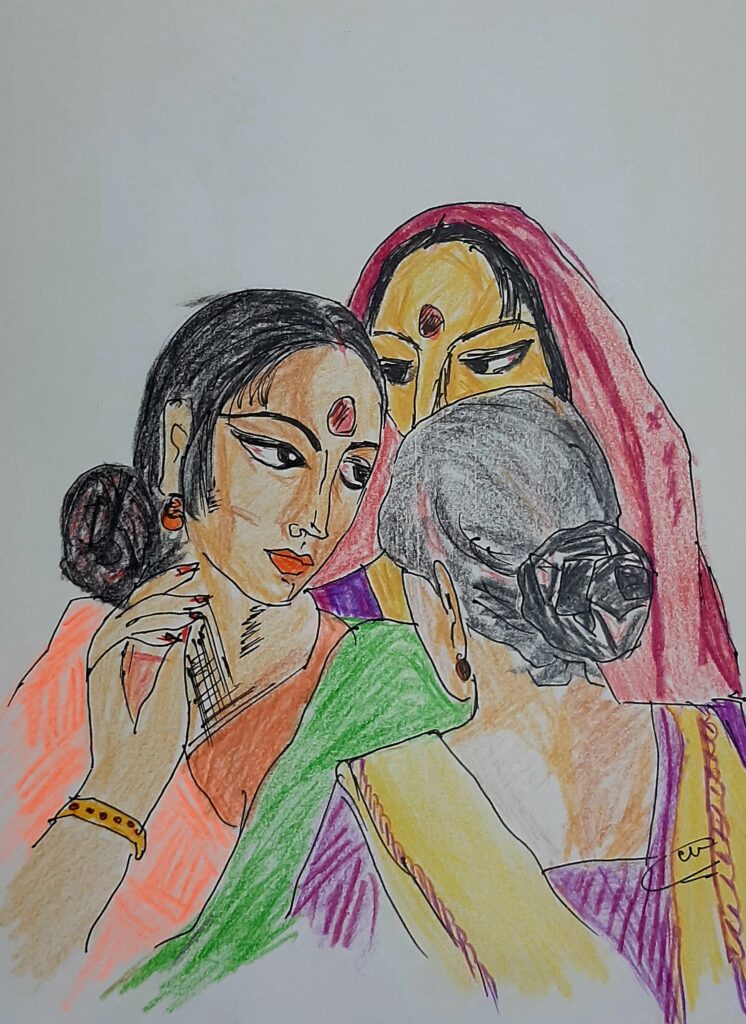

However, there were still a lot of areas of struggle for the LGBTQ+ community in India, for example, in recognising relationship status for same sex couples. This was met with stiff opposition that led to coercive therapies, forced separation or forced marriages and state custody. In the absence of any legal recognition of long-term LGBTQ+ relationships, surviving partners were disregarded when it came to claiming insurance or employment-related benefits, nominee rights for healthcare or even share of property.

In 2022, several Writ Petitions seeking marriage equality for LGBTQ+ couples were submitted in the High Courts and the Supreme Court of India. The key asks were that LGBTQ+ persons should have a “Right to Marry” the person of their choosing, regardless of religion, gender and sexual orientation; and that the Special Marriage Act (1954), which enabled two people of different religions or castes to marry, should also include LGBTQ+ couples by using gender-neutral terminology; likewise, the petitions called for changing the Foreign Marriages Act (1969). In addition, the petitions also called for changes in the Child Adoption laws and regulations to enable LGBTQ+ couples to adopt children together; one petition asked for the right to ‘chosen families’. The final ask was for preventive and protective measures by district and police authorities to ensure the safety of adult consenting LGBTQ+ couples from the violence they faced from their birth families.

The Supreme Court ruling and its impact

The petitions were all clubbed together and came up before a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court that gave its verdict on the 17th of October 2023 (Supriyo@Supriya Chakrabarty and Ors vs Union of India), denying the claim for marriage equality. Although all five judges accepted that any two people have the right to live and build a life together and that such relationships should be protected from violence and discrimination by the State, they failed to reach a consensus on giving queer couples the status of a legally recognised “civil union”. Three of the judges argued that any legal status to such unions can only be granted through enacted legislation. Disappointingly, all five judges unanimously found that there is no “fundamental right to marry” within the Constitutional framework, a position that is in contradiction with Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that recognizes the right to marry and start a family. The court refused to propose any change to the Special Marriage Act (1954) or Foreign Marriage Act (1969) to make the terms gender-neutral, on the grounds that this would be intruding into the legislative domain.

On the issue of transgender persons, all five judges agreed with the proposition that a transgender man has the right to marry a cisgender woman under current laws; similarly, a transgender woman has the right to marry a cisgender man. A transgender man and a transgender woman can also marry. Intersex persons who identify as a man or a woman and seek to enter into a heterosexual marriage would also have a right to marry.

The minority opinion said the LGBTQ+ community has a fundamental right to form relationships and that the state was obligated to recognise and grant legal status to such unions, so that same-sex couples could avail the material benefits provided under the law. The right to choose a partner was the most important life decision. This right goes to the root of the right to life and liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The minority judgement went ahead to declare that not granting the same rights as those that accrue within marriage to those in civil unions would be violative of the Constitutional promise of no discrimination on the basis of sex. Regarding the Child Adoption issue, the minority opinion was that adoption Regulations discriminate against unmarried couples.

In terms of protection from harassment by families and the police, the Chief Justice of India made very compelling directions to the State to protect the rights of LGBTQ+ couples against discrimination and harassment, especially by the police. Even in the absence of formal marriage rights, this specific instruction for law enforcement agencies could go a long way in easing the problems faced by couples exercising their choice of intimate partner, especially lesbian, bisexual, intersex and trans women. This is something that needs to be widely spoken about.

What will the future look like for the LGBTQ+ community in India?

Despite not granting new rights to the LGBTQ+ community, the judicial discourse has certainly moved ahead in terms of recognizing the various forms of discrimination acknowledged earlier in NALSA and Navtej Johar. The Constitution Bench firmly countered the government’s claims that queerness was an alien, urban or elite phenomenon, asserting “pluralistic social fabric” and an “integral part of Indian culture”. All judges acknowledged the inequity and intolerance faced by the LGBTQ+ community, as well as the denial of access to certain benefits and privileges that are available to heterosexual married couples.

In other gains, the State had volunteered to set up a committee chaired by the Cabinet Secretary for the purpose of defining the scope of entitlement of queer couples who are in unions. They may pass an Act creating civil unions, or a domestic partnership legislation, or perhaps, rather than the Union Government, the State legislatures could take action and enact laws or frameworks. The possibilities are not encouraging, however, given the government has already expressed that same-sex marriages are not “comparable with the Indian family unit concept of a husband, a wife and children”.

The split verdict is a clear setback to the long struggle for equal rights of the LGBTQ+ communities, who remain unsure about how far the conservative forces will take up the directions of the Court to bring about the much-needed changes. It is imperative to continue to discuss and engage with familiar and unfamiliar groups and social institutions. This fight shall continue until no one can deny the rights that are due to the LGBTQ+ community as equal citizens of the country.