This research report from the Arab Institute for Women explores definitions of backlash, and how backlash should be understood in Lebanon. […]

De-democratisation in South Asia weakens gender equality

This year, millions of people in South Asia head to the polls. Potential outcomes of elections in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, however, do not bode well for women’s rights or gender equality, says Countering Backlash researcher, Sohela Nazneen. The road ahead is difficult for women’s and LGBTQ+ struggles, as autocratic leaders consolidate power, and right-wing populists, digital repression, and violence against women and sexual minorities are all on the rise

Repression of civic space

CIVICUS is a global alliance of civil society organisations that aims to strengthen citizen action. After the Bangladesh government’s repression of opposition politicians and independent critics in the run-up to the country’s January elections, CIVICUS downgraded Bangladesh’s civic space, rating it as ‘closed’. India and Pakistan it ranked as ‘repressed’.

All three countries recently passed cybersecurity laws and foreign funding regulations that obstruct women’s rights, and feminist and LGBTQ+ organising. In Bangladesh, the ruling Awami League – in power since 2008 – boycotted by the main opposition party during the most recent elections. In India, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), in power since 2014, has systematically undermined democratic institutions and built a Hindu-nationalist base. Pakistan has experienced multiple military forays into elections and politics that effectively limited competition between parties.

When it comes to gender equality concerns, however, these three South Asian countries feature contradictory trends. All have, or had, powerful women heads of government. Former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, and current PM Sheikh Hasina have led Bangladesh; in Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto governed from 1993–1996. Indira Gandhi governed India from 1966 to 1977, and there have been many other regional party heads. During this period, things have improved for ordinary women. Women live longer, more women receive greater education, and they are increasingly active and visible in the economy.

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have all been governed by women leaders. But these countries still experience strong pushback against women’s rights from conservative forces

But persistent gender inequalities remain. Violence against women in public places and within the home is high. Women’s sexuality is subject to heavy policing, and there is strong pushback against women’s rights and gender equality from conservative right-wing-populist forces.

At the Institute of Development Studies, we have been tracking backlash and rollback on rights in the region through two programmes: Sustaining Power and Countering Backlash. Our exploration of the links between a rollback in women’s rights and autocratisation shows specific manifestations of gender backlash.

Bodies as battlegrounds: direct assaults and hollowing-out policies

Women’s bodies have always been policed, and the rights of sexual minorities are highly contested in South Asia. Recent years have seen an increase in direct assaults against feminist and LGBTQ+ activists in online and physical spaces. In all three countries, right-wing political parties and religious groups have mobilised a strong anti-rights rhetoric to oppose critical women’ rights, feminists, and LGBTQ+ activists.

But the battle over women’s bodies is also visible in policymaking. In Bangladesh, for example, sexual and reproductive health, previously framed in terms of rights, have become more technical. In 2011, the government introduced a National Women’s Development Policy, which gave women equal control over acquired property. But mass protests by Islamist groups claiming this clause violated Shariah laws forced the government to backtrack.

Islamist protests against a proposed new policy giving women equal control over acquired property forced the government to backtrack

Women’s rights groups lost their relevance to the ruling elites as the country shifted towards a dominant party state and their support was not needed keep the elites in power. These elites now seek to contain opposition from religious and conservative political groups, whose support is crucial to remain in power. To consolidate its power, the authoritarian Awami League – one of the biggest parties in Bangladesh – needs to appease conservative forces. This limits the avenues for feminist activists to engage in policy spaces, as they have done since Bangladesh’s democratic transition in 1991.

State patronage, gender, and de-democratisation

The pushback against gender equality is not limited to sexuality or the policing of women’s bodies. Populist right-wing political parties have framed women’s economic empowerment in ways that promote the traditional role of women as carers and nurturers, in line with conservative cultural traditions.

Populist right-wingers frame women’s economic empowerment in ways that promote their traditional role as carers and nurturers

In India, the Modi government rolled out various development schemes targeting women. These included free stoves and natural gas cylinders for women, and maternity benefit schemes. Of course, these succeeded in attracting the female vote – but they also helped tie women to their traditional social roles. India heads to the polls in April and May. Election fever is intensifying. At the same time, the BJP’s paternalistic empowerment rhetoric is focusing increasingly on the role of women as nation builders.

In Bangladesh, women workers dominate the country’s main foreign exchange earning industry: ready-made garments. Before the elections, garment workers were engaged in negotiations demanding higher wages. When negotiations failed, police made violent clampdowns on the resulting protests. To consolidate its power in a hotly contested election, the ruling Awami League chose to back the garment factory owners, who hold a majority in parliament.

Protests, politics and repression

The introduction of cybersecurity laws and tightened regulations over NGO funding leave limited space for dissent. Activists and rights-based organisations risk fines, arrests, imprisonment, judicial and online harassment.

Nevertheless, we are still seeing a surge in women-led protests and feminist and LGBTQ+ activism. Protesters are using innovative strategies that disrupt everyday order. These include roadblocks, sit-ins, and theatre performance, graffiti, poetry, and songs to reclaim notions of citizenship and national belonging. The Aurat March is a feminist collective that organises annual International Women’s Day rallies to protest misogyny in Pakistan. Last year, it captured the imagination of a new generation to dream of a more equitable society.

In 2019–2020, Indians rose up against proposed amendments to the Citizenship Act that would offer an accelerated path to citizenship for non-Muslims. The Shaheen Bagh protests, led by Muslim women, saw diverse groups coming together to reclaim the notion of a secular India. Anti-rape protests in Bangladesh led by young feminist groups drew attention to archaic laws, and demanded safety for all types of bodies and genders. These are only a few examples. Yet despite their effort to reclaim public spaces, activists had no sustainable effect on countering state power.

These protests are vital spaces in which citizens can begin to imagine different kinds of polity, and to cherish ideals of democracy. They also help to re-examine intersectional fault lines within protest movements, and find new forms of solidarity.

This article was first published on ECPR’s political science blog site, The Loop.

Understanding gender backlash through Southern perspectives

Global progress on gender justice is under threat. We are living in an age where major political and social shifts are resulting in new forces that are visibly pushing back to reverse the many gains made for women’s and LGBTQ+ rights and to shrink civic space.

The focus of this year’s UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) calls for ‘accelerating the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls…’. This ‘acceleration’ would be welcome indeed. We are not so much worried about slow progress but rather by the regress in a tidal wave of patriarchal – or gender – backlash, with major rollbacks of earlier advances for women’s equality and rights, as well as by a plethora of attacks on feminist, social justice and LGBTQ+ activists, civic space and vulnerable groups of many stripes.

The Countering Backlash programme explores this backlash against rights in a timely and important IDS Bulletin titled ‘Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives’. In it, we ask ‘how can we better understand the contemporary swell of anti-feminist (or patriarchal) backlash across diverse settings?’. We present a range of perspectives and emerging evidence from our programme partners from Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Kenya, Lebanon, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.

Here’s what you can find in our special issue of the IDS Bulletin.

Why we need to understand gender backlash

‘Anti-gender backlash’, at its simplest, it refers to strong negative reactions against gender justice and those seeking it. Two widely known contemporary examples, from different contexts, are Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill (passed in 2023), and the United States Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe vs Wade (which gave women the constitutional right to abortion) in 2022.

The term ‘backlash’ was first used in Susan Faludi’s (1991) analysis of the pushback against feminist ideas in 1980s in the United States, and historically, understandings of anti-gender backlash have been predominantly based on experiences and theorising about developments in the global north. More recent scholarship has afforded insights on and from Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Much explanatory work to date, if it does not implicitly generalise from global north experience, often fails to adequately engage with the ways these locally specific phenomena operate transnationally, including across the global south, and with its complex imbrication in a broader dismantling of democracy.

New ways of analysing gender backlash

The Issue presents new ways of analysing backlash relevant to diverse development contexts, grounded examples, and evidence of anti-gender dynamics. It aims to push this topic out of the ‘gender corner’ to connect it to contemporary shifts in relationships between faith, identity and state, governance, and the broader politics of democracy and economics, as seen from across the global south.

The articles in this special issue are grouped into three themes: one, on ‘voice and tactics’, including whose voices are being heard, and what tactics are being used?; two, on ‘framings and direction’, including how are ideologies spread, and how can we understand attitudes to change? and; three, on ‘temporality and structure’, including what is ‘back’ about backlash? What and who drives it, and how is it imbricated in broader trends and crises? Additionally, most articles proffer some thoughts and recommendations on the implications for directions to counter backlash, whether specifically for feminist movements, for other gender and social justice defenders, or for researchers and students.

Southern Perspectives

This Issue fundamentally challenges simple and reductive understandings of gender backlash. Diverse examples of politicised backlash are ‘mapped’ across geographies and viewpoints. This can help to build a more granular and multi-perspectival understanding of backlash, of its more subtle processes of co-optation and division, its connected across borders, regions, and continents, and the contextual and different strategies of resistance.

Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives

The 30th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995, and the 10th anniversary of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are fast approaching. And with global progress on gender justice on the rise around the world, we must find ways to combat gender backlash now.

The Countering Backlash programme has produced timely research and analysis on gender backlash, presenting a range of perspectives and emerging evidence on backlash against gender justice and equality, as such phenomena manifest locally, nationally, and internationally.

‘Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives’ is our iteration of the IDS Bulletin, including contributions, insights, expert knowledge from a range of actors in diverse locations across South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, Lebanon and the UK – and all part of the Countering Backlash programme.

The IDS Bulletin addresses the urgent question of how we can better understand the recent swell of anti-gender backlash across different regions, exploring different types of actors, interests, narratives, and tactics for backlash in different places, policy areas, and processes.

The IDS Bulletin will be launched by a hybrid event on 07 March 2024, ahead of the programme’s attendance at UN Women’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) 2024.

Articles

Jerker Edström; Jennifer Edwards; Chloe Skinner; Tessa Lewin; Sohela Nazneen

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Sohela Nazneen

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Cecília Sardenberg; Teresa Sacchet; Maíra Kubík Mano; Luire Campelo; Camila Daltro; Talita Melgaço Fernandes; Heloisa Bandeira;

Nucleus of Interdisciplinary Women’s Studies of the Federal University of Bahia (NEIM)

Maheen Sultan; Pragyna Mahpara

BRAC BIGD

Adeepto Intisar Ahmed; Ishrat Jahan; Israr Hasan; Sabina Faiz Rashid; Sharin Shajahan Naomi

BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health

Jerker Edström

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Abhijit Das; Jashodhara Dasgupta; Maitrayee Mukhopadhyay; Sana Contractor; Satish Kumar Singh

Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ)

Shraddha Chigateri; Sudarsana Kundu

Gender at Work Consulting – India

Phil Erick Otieno; Alfred Makabira

Advocates for Social Change Kenya (ADSOCK)

Amon A. Mwiine; Josephine Ahikire

Centre for Basic Research

Tessa Lewin

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Nay El Rahi; Fatima Antar

Arab Institute for Women (AIW)

Jerker Edström, Jenny Edwards, Tessa Lewin, Rosie McGee, Sohela Nazneen, Chloe Skinner

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Event: Sustaining and expanding south-south-north partnerships and knowledge co-construction on global backlash to reclaim gender justice

We are living in a time of global unrest and division stoked by increasing polarisation in politics, authoritarianism and backlash on gender equality, inclusion and social justice.

This event, during the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) 2024, explored how effective south-south-north partnerships can develop better and more nuanced understandings of gender backlash, to inform strategies for defending gender justice.

Based on research from the Countering Backlash programme, this event was a discussion between researchers, civil society activists, with bi- and multi-lateral development agencies. It provided insights from research and policy spaces on how we can work together more effectively to reclaim gender justice.

Starting in a panel format, speakers were asked to reflect on key insights from partnering in research on backlash, in activism and in international policy spheres. The co-chairs facilitated a dialogue between panellists and then opened up the discussion with the audience.

This event was hosted by the Lebanese American University, and co-sponsored by the Government of Sweden.

When

- 13 March 2024

- 12:00-14:00 EST // 16:00 – 18:00 UK Time

Where

- In person – Lebanese American University, New York

- Online – WebEx

Speakers

- Nay El Rahi, Activist and Researcher, Arab Institute for Women, Lebanese American University

- Phil Otieno, Executive Director, Advocates for Social Change Kenya (ADSOCK)

- Tessa Lewin, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

- Jerker Edström, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

- Ida Petterson, SIDA – Sweden

- Karen Burbach, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands

- Constanza Tabbush, Research Specialist, UN Women

Co-chairs

- Myriam Sfeir – Arab Institute for Women, Lebanese American University

- Sohela Nazneen – Institute of Development Studies

Event: How is backlash weakening institutional contexts for gender justice globally?

Gender backlash is continually gaining momentum across the globe, and social and political institutions and policies are being dismantled. Gender justice activists and women’s rights organisations are having to mobilise quickly to counter these attacks.

With speakers from Bangladesh, Uganda, Lebanon, Serbia and India, in this official NGO CSW68 event we asked, ‘how is gender backlash weakening institutional contexts for gender justice globally?’ Speakers discussed: stalling and lack of implementation of the Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Act (2010) in Bangladesh; the infiltration of conservative religious and political actors in democratic institutions in the context of Serbia and neighbouring countries; anti-feminist backlash as institutional by default in Lebanon; and the legislative weakening of institutional contexts in Uganda, examining Acts which exert control over Civil Society Organisations.

When

- 11 March 2024

Speakers

- Pragyna Mahpara, BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD)

- Sandra Aceng, Executive Director, Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET)

- Nay El Rahi, Activist and Researcher, Arab Institute for Women (AIW)

- Nađa Bobičić, Researcher, Center for Women’s Studies Belgrade (CWS)

- Santosh Kumar Giri, Director, Kolkata Rista

-

Jerker Edström, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Chair

- Chloe Skinner, Research Fellow, IDS

Partner Event: BRAC JPGSPH and BIGD hosts Stakeholder Roundtable on Online Anti-Feminist Backlash

Countering Backlash partner BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health (BRAC JPGSPH) held a roundtable discussion on ‘Anti-feminist Backlash in Online Spaces and Creating Counter-Moves’ in collaboration with BRAC Institue of Governance and Development (BIGD) in Dhaka, Bangladesh on 28th November, 2023.

The roundtable was moderated by Nazia Zebin who is the Executive Director of Oboyob, a community-based organisation tackling gender justice for sexual minorities. The event featured research presentations by Raiyaan Mahbub and Israr Hasan from BRAC JPGSPH and Iffat Jahan Antara from BIGD which set the context for the discussion. The discussions focused on the current challenges of navigating gender justice agendas in the face of rising organised backlash and the delegitimisation of feminism in the consciousness of the mass populace on social media platforms.

Online violence against women is real violence

The campaign for 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence this year encourages citizens to share the actions they are taking to create a world free from violence towards women. But what is being done about the online misogyny and violence encountered by gender justice activists, individuals, and organisations fighting for women’s rights and creating awareness online? Do our laws, the state, and its citizens consider an action to be gender-based violence only when it results in physical harm, rape, sexual assault, murder, or something severe?

Every day, women of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds become victims of online harassment and abuse in the form of trolling, bullying, hacking, cyber pornography, etc. Although there is no nationally representative data on victims of online gender-based violence, according to Police Cyber Support for Women, 8,715 women reported being subjected to hacking, impersonation, and online sexual harassment from January to November 2022.

Read the full op-ed by Countering Backlash partner BRAC BIGD on ‘The Daily Star’ website.

বাংলাদেশের পারিবারিক সহিংসতা আইন বাস্তবায়নে নেতিবাচক প্রতিক্রিয়া (ব্যাকল্যাশ) প্রতিরোধ

নারী ও শিশু নির্যাতন দমন আইন এবং পারিবারিক সহিংসতা (প্রতিরোধ ও সুরক্ষা) আইন ২০১০- এর মতো আইন থাকা সত্ত্বেও বাংলাদেশে পারিবারিক সহিংসতার হার অনেক বেশি। বাংলাদেশ পরিসংখ্যান ব্যুরোর তথ্য অনুযায়ী, প্রতি পাঁচজন নারীর মধ্যে প্রায় তিনজন (৫৭.৭%) তাদের জীবদ্দশায় কোনো না কোনো ধরনের শারীরিক, যৌন বা মানসিক সহিংসতার শিকার হয়েছেন। […]

Countering Backlash in the Implementation of Bangladesh’s Domestic Violence Act

Domestic violence rates are high in Bangladesh in spite of laws such as the Nari o Shishu Nirjatan Domon Ain and the DVPPA 2010. According to data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, almost three in every five women (57.7%) have experienced some form of physical, sexual, or emotional violence in their lifetime. […]

Event: Counting the cost: funding flows, gender backlash and counter backlash

Major political and social shifts are stifling the possibility of gender justice across the world. Analysing this backlash as operating on global, regional and local scales in this webinar, we ask, where is the money?

While predominant anti-gender backlash movements and actors appear well financed, those countering backlash face significant financial challenges, heightened in the context of rising authoritarianism and shrinking civic space.

In this event, we were joined by leading experts and partners from Countering Backlash and beyond. Isabel Marler from the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) presented a mapping of sources of funding for anti-rights actors, and interrogate what is effective in countering anti-rights trends, while Lisa VeneKlasen (Independent Strategist, Founder and Former Executive Director of JASS), explored ‘where is philanthropy on anti-gender backlash’? Turning to national restrictions, Sudarsana Kundu and Arundhati Sridhar from our partner organisation Gender at Work Consulting – India focused on the impacts of funding laws for women’s rights organising in India.

When

- 12 December 2023

- 13:00 – 14:30 UK time

Speakers

- Lisa VeneKlassen, Independent Strategist, Founder and Former Executive Director of JASS (Just Associates)

- Isabel Marler, Lead, Advancing Universal Rights and Justice, Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID)

- Sudarsana Kundu, Executive Director, Gender at Work Consulting – India

- Arundhati Sridhar, Gender at Work Consulting – India

Discussant

- Rosie McGee, Research Fellow, IDS

Chair

- Chloe Skinner, Research Fellow, IDS

Watch the recording

Partner event: BIGD discuss the implementation of Bangladesh’s Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Act

Countering Backlash partner BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) hosted an engaging and important workshop with representatives of the Bangladesh Government and advocates. The workshop was hosted by BIGD in partnership with the Citizen’s Initiative against Domestic Violence (CIDV) at the BIGD offices in Dhaka’s Azimur Rahman Conference Hall.

The session discussed the implementation of the Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Act (DVPPA) 2010, and shared key findings and recommendations from BIGD’s Countering Backlash policy brief ‘Backlash in Action? Or Inaction? Stalled Implementation of the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010 in Bangladesh‘. Despite being approved in 2010, the Act remains underutilized and commitment to its implementation has been low, often treating domestic violence as a family matter. There is an immediate need for changed norms and attitudes among those who are implementing the Act, along with better victim support, procedural revisions for effective implementation of the DVPPA.

The session featured a presentation by Maheen Sultan, Senior Research Fellow, and Pragyna Mahpara, Senior Research Associate, both from BIGD. Expert insights were provided by Dr Shahnaz Huda, Professor of Law at the University of Dhaka.

The event offered crucial insights and perspectives, emphasizing the ongoing effort to combat domestic violence and create a safer environment for all.

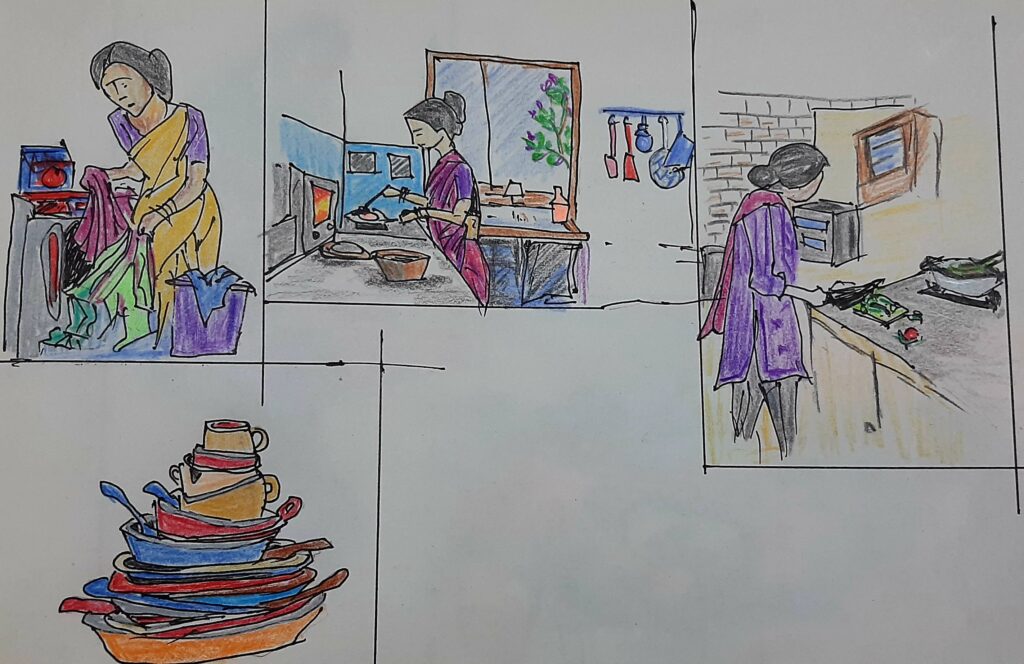

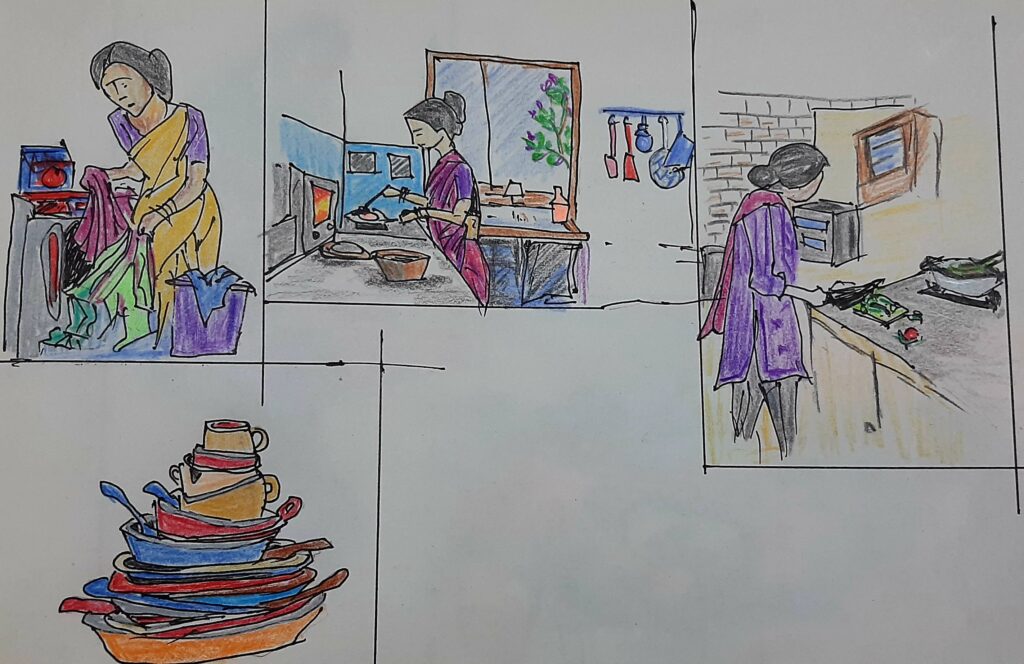

Reversing Domestic Workers’ Rights: Stories of Backlash and Resilience in Delhi

‘Reversing Domestic Workers’ Rights: Stories of Backlash and Resilience in Delhi’ is a timely and important new ‘storybook’ produced by Gender at Work Consulting – India. It shares 12 stories from domestic workers living in Delhi NCR, and the often-tragic tales of their lives. […]

Women domestic workers in India are demanding respect. Here’s Sundari’s story

Women domestic workers have been severely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. In India, Countering Backlash partner Gender at Work Consulting – India have been collaborating with domestic workers in Delhi and compiling their stories into a storybook, launching on 24 July 2023.

India’s women domestic workers are demanding justice. Anita Kapoor, co-founder of the Shahri Mahila Kaamgar Union (SMKU – Urban Women Worker’s Union), argues that ‘it is important for domestic workers to speak together about what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and about the issues that we continue to face to this day.’ Here is Sundari’s* story, prepared by Chaitali Haldar, an independent researcher and trainer, with the support of SMKU.

A life of struggles in the city

Sundari was 20 when devastating floods forced her and her family to seek a fresh start in Delhi. Their financial situation was proving difficult with only her husband’s earnings, so Sundari took a few cleaning jobs. None of the work arrangements were long-term, so she was stuck in a cycle of losing jobs and searching for new ones. For women, especially those who are migrants and from a ‘lower’ caste, finding well-paid, long-term employment is difficult.

The slum in which Sundari and her family lived was demolished due to the Delhi’s so-called ‘beautification’ plans, and their lives were disrupted again. Sundari’s children were forced to leave their school as it was now too far away, and she was struggling to find new schools for them as they did not have the necessary documents. She also had to search for a new job again, now with the added challenge of being in an unfamiliar part of the city. Sundari’s sense of stability was shattered.

Sundari continued her daily struggle to provide for her family and managed, after much searching, to secure a job as a cook in a household. However, the employment did not last long as Sundari injured her leg as was let go of. Although India’s Employment State Insurance (ESI) scheme was extended in 2016 to include domestic workers, their eligibility for medical benefits is limited. Accessing these benefits under the scheme remains challenging for domestic workers.

Challenges faced due to Covid-19

At the age of 56, Sundari, as with most women in India, faced an unprecedented challenge in the form of Covid-19. Reports show that only 19% of women remained employed during the first lockdowns in 2020. During this time, it was near impossible for domestic workers to find employment. Any attempt Sundari made to secure employment was rejected, either due to her age or because she did not yet have the Covid-19 vaccine. On top of this, Sundari’s struggles were worsened by her husband’s declining health. Just before the start of the pandemic, Sundari’s son was helping her, and her husband, complete the government’s pension scheme forms. This would have enabled them to access monthly financial support from the state. However, he became addicted to alcohol and was not able to submit the forms before the first lockdown was imposed and it became impossible to submit them. This continuous cycle of financial crisis left Sundari and her family in a state of perpetual uncertainty.

It was after the lockdowns were imposed that Sundari began associating with the SMKU. They provided Sundari and her family with ration supplies and cooked meals, which was vital for them at this time.

Sundari’s struggles continue

In 2022, Sundari was able to find and secure employment at a private school in Badarpur, southeastern Delhi, but she was not happy there. The school’s principal bickered continuously with Sundari and imposed numerous constraints on her, limiting her work. At the start, she often contemplated resigning but felt that she could not, due to her financial situation. Sundari was constantly reminded that if she were to abandon her employment, they would struggle to afford her husband’s much-needed medication, so she persevered.

However, over time, Sundari lost her job at the private school. At the same time, her husband’s health deteriorated significantly, requiring him to undergo treatment at hospital. Sundari spent many hours by her husband’s side, while the medical bills piled up. It was becoming difficult to manage the hospital fees and food expenses for Sundari and her husband.

From the devastating floods in her village, to the wave of displacement in the city, the challenges in Sundari’s life felt relentless. She felt stuck in a web of challenges, each one more daunting than the last.

While for many individuals a sense of normalcy has returned post the pandemic, the circumstances for women domestic workers remain exceptionally precarious. Many of them are having to rebuild their lives, intensifying their vulnerability and marginalisation.

*Name changed to protect the person’s identity

This story was originally written in Hindi (translation provided by Sudarsana Kundu and Shraddha Chigateri from Countering Backlash partner organisation Gender at Work Consulting – India).

सुंदरी की कहानी : गाँव में बाढ़ से लेकर शहर के विस्थापन तक संघर्षों से भरी एक शहरी महिला कामगार की ज़िंदगी

भारतीय घरेलू कामगार न्याय की मांग कर रहे हैं। शहरी महिला कामगार यूनियन (एसएमकेयू) की सह-संस्थापक, अनीता कपूर बताती हैं कि ‘घरेलू कामगारों के लिए यह महत्वपूर्ण है कि वे एक साथ मिलकर उन मुद्दों के बारे में बारे में बात करें जो कोविड-19 महामारी के दौरान हुआ जिसका सामना वे आज भी कर रहे हैं। यह सुंदरी की कहानी है, जो एसएमकेयू के समर्थन से चैताली हलदर द्वारा लिखित और स्वाती सिंह द्वारा संपादित की गई है।

बिहार के मधुबनी ज़िले की रहने वाली सुंदरी केवट जाति के एक निम्नवर्गीय परिवार से है। परिवार में माता-पिता, दो बहन और एक भाई है। शुरुआती दौर में उसके माता-पिता बेलदारी का काम करके परिवार का पेट पालते थे। आर्थिक तंगी की वजह से सुंदरी सिर्फ़ पाँचवी कक्षा तक ही पढ़ाई कर पायी। इसके बाद अचानक हुए पिता के देहांत ने सुंदरी और उसके परिवार के जीवन का समीकरण ही बदल दिया। सुंदरी तब पंद्रह साल की थी जब पिता के देहांत के बाद उसकी शादी करवा दी गयी। पढ़ाई करने व स्कूल जाने की उम्र में ससुराल की ज़िम्मेदारी उसके नाज़ुक कंधों पर डाल दी गयी।

गाँव में बाढ़ से लेकर शहर के विस्थापन तक संघर्षों भरी ज़िंदगी

सुंदरी बीस साल की थी जब गाँव में आयी भयानक बाढ़ से उसके परिवार से रहने के लिए छत और पेट पालने के लिए रोज़गार का साधन भी छिन गया। उनके पास रोज़गार की तलाश में अब शहर जाने के अलावा और कोई उपाय नहीं था, इसलिए सुंदरी और उसके पति अपने एक बेटे और दो बेटी के साथ दिल्ली आ गए। इस दौरान सुंदरी ये समझ चुकी थी कि इस बड़े शहर में अकेले पति की कमाई से परिवार का पेट पालना मुश्किल होगा। इसलिए उसने आसपास की कोठियों में झाड़ू-पोछा और बर्तन का काम करना शुरू किया। कुछ समय बाद सुंदरी को अपने परिवार के साथ गौतमनगर में आकर बसना पड़ा। यहाँ भी सुंदरी कोठियों में काम करती रही लेकिन उसे यहाँ काम मिलता भी रहा और छूटता भी रहा।

इसी बीच साल 1999 से साल 2000 के बीच में सुंदरीकरण के नामपर गौतमनगर की भी झुग्गी तोड़ दी गयी और यहाँ रहने वाले लोगों को गौतमपुरी में विस्थापित कर दिया गया। ये विस्थापन अपने आप में एक बुरा अनुभव था। सुंदरी का परिवार मानो अस्त-व्यस्त हो गया। बच्चों की पढ़ाई और जान-पहचान वालों व रिश्तेदारों से नाते टूट गए। बच्चों के स्कूल से उनके काग़ज़ात भी नहीं मिल पाए, जिसके चलते उन्हें आगे पढ़ाई से जुड़ने में ढ़ेरों कठिनाइयों का सामना करना पड़ा। सुंदरी का सभी काम भी छूट गया। इस विस्थापन ने एक़बार फिर उसके परिवार को असुरक्षित ज़िंदगी जीने को मजबूर कर दिया। अब उसे एकबार फिर से काम की तलाश करनी पड़ी, जो अपने आप में किसी चुनौती से कम नहीं था। इसके बाद धीरे-धीरे हर दिन के संघर्षों के साथ उसकी ज़िंदगी बीतने लगी। सुंदरी लॉकडाउन से पहले एक कोठी में खाना बनाने का काम करती थी। कोठी में काम करते हुए एकदिन सुंदरी के पैर में चोट लग गयी और उसकी मालकिन ने उसकी मदद भी की। लेकिन इसके बाद दुबारा उसे काम पर नहीं रखा।

कोरोना महामारी से बढ़ी चुनौतियों जूझती सुंदरी

क़रीब 56 साल की उम्र में सुंदरी की ज़िंदगी में कोरोना महामारी का दौर एक बड़ी चुनौती के रूप में सामने आया, जब उसके परिवार की स्थिति बहुत ज़्यादा ख़राब हो गयी। सुंदरी के सारे काम छूट गए और घर में आर्थिक तंगी बढ़ने लगी। ऐसे में जब सुंदरी काम की तलाश में कोठी में जाती तो मालकिन उसे ये बोलकर भगा देती कि ‘पहले वैक्सीन लेकर आओ।‘ ज़्यादा उम्रदराज होने की वजह से भी लोग उसे काम नहीं देते थे। इस दौरान उसके पति की तबियत ख़राब होने की वजह से उसका काम भी छूट गया। सुंदरी के बेटे के पास एक अच्छी नौकरी थी, लेकिन उसने नौकरी छोड़कर रिक्शा चलाने का काम शुरू कर दिया था। साथ ही, बेटे को नशे की लत भी लग चुकी थी, जिसके चलते सुंदरी को अपने बेटे से किसी भी तरह की आर्थिक मदद की कोई उम्मीद नहीं थी। बेटे का अपना परिवार था, जिसकी ज़िम्मेदारी उसपर थी। लेकिन इसके बावजूद वो दो दिन रिक्शा चलाने के बाद घर काम बंद करके बैठ जाता, जिससे परिवार में लगातार आर्थिक तंगी बनी रहती थी।

कोरोना से पहले सुंदरी के पति ने अपने बेटे को अपना और सुंदरी का वृद्धा पेंशन का फार्म भरकर जमा करने के लिए दिया। पर लापरवाह बेटा उस फार्म को घर में रखकर दारू पीने में लग गया और फिर इसके बाद लॉकडाउन शुरू हो गया, जिसकी वजह से उन्हें इस दौरान वृद्धा पेंशन भी नहीं मिल पायी। कोविड के इस कठिन समय में सुंदरी का जुड़ाव शहरी घरेलू कामगार यूनियन से हुआ, जिनकी मदद से उसे और उसके परिवार को कच्चा राशन और पके हुए खाने की भी मदद मिली थी।

विस्थापन और आर्थिक तंगी से ज़ारी सुंदरी का संघर्ष

साल 2022 में सुंदरी ने बदरपुर के एक प्राइवेट स्कूल में काम करना शुरू किया पर वो इस काम से खुश नहीं थी। स्कूल की प्रिंसिपल उसके साथ बहुत किच-किच करती थी। उसे हर बात पर रोक-टोक लगाती थी। ऐसे में सुंदरी के मन में बहुत बार ये ख़्याल आया कि वो ये काम छोड़ दे। लेकिन इसी ख़्याल के साथ उसके ज़हन में अपने बीमार पति और घर की आर्थिक तंगी की तस्वीर सामने आ जाती, जिसे याद करके सुंदरी के मन में ख़्याल आया कि अगर वो ये काम भी छोड़ देती है तो पति की दवाइयों का खर्च कैसे लाएगी। इसलिए उसने बेबस होकर अपने इस काम को जारी रखा।

किन्हीं कारणवश कुछ समय बाद सुंदरी का वो काम भी छूट गया। इससे उसकी आर्थिक स्थिति और भी ज़्यादा बुरी हो गयी। उसका पति बहुत बीमार है और हॉस्पिटल में उसका डायलिसिस चल रहा है। सुंदरी को भी अपने पति के साथ हॉस्पिटल में ही रहना पड़ता है। खाने और हॉस्पिटल के खर्च का जुगाड़ करने में उसके ऊपर क़र्ज़ का भार लगातार बढ़ता जा रहा है। ऐसा लगता है मानो सुंदरी की ज़िंदगी से कठिनाइयाँ कम होने का नाम ही नहीं ले रही है, ढलती उम्र के साथ उसपर चुनौतियों का भार लगातार बढ़ता जा रहा है। गाँव में बाढ़ से लेकर शहर में विस्थापन के साथ ज़ारी संघर्ष में खुद को सँभालना, पति की बीमारी और ग़ैर-ज़िम्मेदार लापरवाह बेटे के साथ सुंदरी की ज़िंदगी उलझ-सी गयी है।

Backlash in Action? Or Inaction? Stalled Implementation of the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010 in Bangladesh

This paper explores the lax implementation of the Domestic Violence Act, and how it is effecting gender backlash in Bangladesh. It also examines how women’s rights organisations have articulated feminist voices in terms of agenda and framing and used collective agency to counter the pushback. […]

Women domestic workers in India are demanding respect. Here’s Roopali’s story

Women domestic workers have been severely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. In India, Countering Backlash partner Gender at Work Consulting – India have been collaborating with domestic workers in Delhi and compiling their stories into a storybook, launching July 2023.

India’s women domestic workers are demanding justice. Anita Kapoor, co-founder of the Shahri Mahila Kaamgar Union (SMKU – Urban Women Worker’s Union), shares how ‘it is important for domestic workers to speak together about what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and about the issues that we continue to face to this day.’ Here is Roopali’s* story, prepared by Chaitali Haldar, an independent researcher and trainer, with the support of SMKU.

Life uprooted

Roopali’s life was disrupted when she was just 12 years old and studying at school. Her home, in the slum of Gautamnagar in Delhi, India, was identified in 1999 as one of the informal settlements to be demolished in the name of redevelopment and so-called ‘beautification’ of the city.

The experience was terrible for Roopali and her family. After their home was demolished, they ended up living next to a railway track with just a tarpaulin sheet as a roof. They were also miles away from the parents’ place of employment and Roopali’s and her siblings’ school.

‘The warp and weft of relationships, friendships, solidarities with our neighbours and families that wove the fabric of our lives together for so many years had been torn asunder by the relocation.’

After months of trying, Roopali’s family were eventually able to buy a small plot of land after fighting through the bureaucratic red tape of government departments. Even though they had lived in a slum before, they had access to basic services such as water and electricity. In the new location they were deprived of the most essential services. Their daily commute to work was 20 kilometres and Roopali’s and her siblings’ education was severely disrupted.

Roopali and her sisters were blocked by their older brother from going to school as he argued that it was ‘too far away’. At the age of 15, Roopali ended up going to work with her mother as a domestic worker, a job that Roopali would do into her adult life.

Connecting with a domestic workers’ union

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Roopali was working in three households. She lost these jobs at the start of the pandemic lockdowns and wasn’t even paid the salary that she was owed. During this time, it was near impossible for domestic workers to find employment.

How can one secure employment if there are no jobs available?

It was during this time that Roopali began associating with the SMKU in Delhi. They were providing an open and safe space for domestic workers to access relief and support during the lockdowns. At the time, the government’s Covid-19 welfare services were only accessible online. SMKU ran an information centre which provided people the latest information on support and relief measures. Through SMKU’s support, Roopali was able to obtain both ration and an e-ration card.

Currently, Roopali is working as a cleaner in a family home, earning around INR 4,000 per month. She was supporting her entire family whilst her husband was looking for work during the pandemic. But this is just a temporary job and she is at risk of losing it once the family find a ‘permanent’ replacement. Since Covid-19, there are fewer jobs available and more employers are now wanting domestic workers to be ‘live-in’ and available 24 hours a day. Roopali is facing this all in the midst of health issues, which have become acute after she experienced a serious workplace related injury, that have led her into significant amounts of debt that she and her husband are struggling to pay off. Her current employer is also threatening to fire her if she takes any more time off due to her health conditions. Roopali feels stuck in a spiral of insecurity and old beyond her years.

I feel distressed. Sometimes I feel defeated by life’s circumstances.

Credit: Mrinalini Godara

Roopali works closely with the SMKU, taking part in activities organised by them, encouraging others to join the union, and sharing her joys and sorrows with her fellow women domestic workers.

*Name changed to protect the person’s identity.

This story was originally written in Hindi (translation provided by Sudarsana Kundu and Shraddha Chigateri from Countering Backlash partner organisation Gender at Work Consulting – India).

रूपाली की कहानी: सम्मान और अधिकार की माँग करती शहरी महिला कामगार

महिला घरेलू कामगार कोविड-19 महामारी से बुरी तरह प्रभावित हुई हैं। भारत में, काउंटरिंग बैकलैश पार्टनर जेंडर एट वर्क दिल्ली में घरेलू कामगारों के साथ सहयोग कर रहा है और उनकी कहानियों को आगामी स्टोरीबुक में संकलित कर रहा है, जो 17 जुलाई को लॉन्च होगी।

बिखरी-सी ज़िंदगी

भारतीय घरेलू कामगार न्याय की मांग कर रहे हैं। शहरी महिला कामगार यूनियन (एसएमकेयू) की सह-संस्थापक, अनीता कपूर बताती हैं कि ‘घरेलू कामगारों के लिए यह महत्वपूर्ण है कि वे एक साथ मिलकर उन मुद्दों के बारे में बारे में बात करें जो कोविड-19 महामारी के दौरान हुआ जिसका सामना वे आज भी कर रहे हैं। यह रूपाली की कहानी है, जो एसएमकेयू के समर्थन से चैताली हलदर द्वारा लिखित और स्वाति सिंह द्वारा संपादित की गई है।

बिखरी-सी ज़िंदगी

उत्तर प्रदेश के बदायूँ ज़िले की रहने वाली रूपाली वाल्मीकि समुदाय से है। तीन बेटे और एक बेटी के साथ उसके माता-पिता सालों पहले काम की तलाश में दिल्ली आ गए थे। दिल्ली में परिवार का पेट पालने के लिए पिता नाली-सफ़ाई का काम करते थे और माँ कोठियों में घरेलू काम करती थी। रूपाली का परिवार अस्सी के दशक में गौतमनगर आकर बस गया। साउथ एक्स की एक कोठी में धीरे-धीर उसकी मम्मी काम करने लगी। पापा को एक ऑफ़िस में काम मिला। उनकी ज़िंदगी चल रही थी। लेकिन इसी बीच रूपाली के पापा का देहांत हो गया। इससे उनके घर की स्थिति बहुत ज़्यादा ख़राब हो गयी।

साल 1999 में जब रूपाली बारह साल की थी और पाँचवी कक्षा में पढ़ती थी, तब ‘सुंदरीकरण’ के नामपर गौतमनगर की झुग्गियों को तोड़ने का सिलसिला शुरू हुआ। इस दौरान उन्हें झुग्गियों से विस्थापित कर गौतमपुरी की बस्तियों में बसाया गया। ये पुनर्वास अपने में बहुत भयावह और तकलीफ़देह था। सालों पहले बसाए बसेरे तोड़ दिए गये। लोगों के रोज़गार चले गए और बच्चों की पढ़ाई बंद हो गयी। दिसंबर की सर्दी में रेलवे लाइन के पास त्रिपाल-पन्नी डालकर रूपाली के परिवार को कई महीनों रहना पड़ा। रूपाली की मम्मी उसे पढ़ाना चाहती थी, लेकिन बड़े भाई ने ये कहकर मना कर दिया कि ‘स्कूल के लिए कौन इतनी दूर जाएगा।‘ इसके बाद उसके परिवार को एक प्लाट को लेकर डीडीए, इंजीनियर और अन्य विभाग के चक्कर काटने पड़े, तब जाकर एक प्लाट का टुकड़ा सात हज़ार रुपए देने के बाद उन्हें मिला। उनकी ज़िंदगी मानो बीस साल पीछे चली गयी थी, क्योंकि सिर्फ़ मकान आने से ज़िंदगी थोड़े ही बदल जाती है। उनकी ज़िंदगी का ताना-बाना बिखर गया था। रिश्ते-नाते सब एक-दूसरे से अलग हो गए थे। भले ही वो झुग्गी-बस्ती थी पर उसकी मम्मी का काम, घर के पास था। स्कूल पास था। पानी-बिजली थी। यहाँ आकर उन्हें इन बुनियादी सुविधाओं के लिए वंचित होना पड़ा और बहुत परेशनियाँ झेलनी पड़ी। रूपाली पंद्रह साल की उम्र से अपनी मम्मी के साथ कोठियों में काम करने के लिए साउथ एक्स ज़ाया करती थी। उसके बाद पंद्रह साल की उम्र में ही उसने अपनी मर्ज़ी से शादी कर ली। ये शादी सिर्फ़ दो साल तक चली। क्योंकि रिश्ते में बहुत तनाव और हिंसा बढ़ गयी थी। वो अपनी मम्मी के घर नौ महीने तक अपने बेटे को लेकर रही। फिर उसने अपनी पसंद से दूसरी शादी कर ली और इस शादी से एक बेटी है। आज रूपाली का बेटा 18 साल और बेटी 9 साल की है।

चुनौतियाँ: शहरों में महिला कामगार होने की

रूपाली आज भी साउथ एक्स में काम करने जाती है। साउथ एक्स में वो पहले चार कोठियों में काम करती थी, जिसमें अब काम कम हो गए है और उसकी महीने की पगार भी मात्र दो-तीन हज़ार ही रह गयी है। इन्हीं पैसों से वो अपने परिवार का गुजर बसर करती है। एकदिन कोठी में काम करते हुए रूपाली को सिर में किसी नुकीली चीज़ से चोट लग गयी और ज़्यादा खून निकलने की वजह से वो बेहोश गयी। इलाज में क़रीब तीस-चालीस हज़ार रुपए खर्च हुए, जिसका भुगतान मालकिन ने किया। लेकिन इसके बाद उन्होंने रूपाली को दुबारा काम पर नहीं रखा। सही तरीक़े से इलाज न होने की वजह से इस चोट के बाद से उसे दिमाग़ से जुड़ी समस्याएँ होने लगी। अक्सर काम के दौरान उसकी स्वास्थ्य से जुड़ी समस्याएँ सामने लगी, जिसका असर उसके काम पर भी होने लगा। काम कम होने लगे और आमदनी भी घटने लगी।

अभी के समय में रूपाली साउथ एक्स में एक कोठी में काम करती है, जहां उसे सिर्फ़ कुछ ही समय के लिए रखा गया है जब तक उसकी मालकिन को दूसरा कुक नहीं मिल जाता। कोविड के बाद से घरेलू काम में आए बदलाव के बारे में रूपाली बताती है कि ‘कोविड से पहले हम घरों-कोठियों में झाड़ू-पोछा और बर्तन का काम करके वापस अपने घर लौट जाते थे। लेकिन कोविड के बाद से सभी लोग चौबीस घंटे के लिए काम पर रखने लगे है, इसलिए खुला काम (रोज़ काम पर आने और वापस जाने का काम) करवाने के लिए अब कोई तैयार नहीं होता है।‘’

मालिक को चौबीस घंटे घरों में रहकर काम करने वाला कामगार चाहिए होता है, जो अब रूपाली के लिए अपने स्वास्थ्य से जुड़ी समस्याओं और परिवार की ज़िम्मेदारियों की वजह से कर पाना मुश्किल है। यही वजह है कि अब घरेलू काम के क्षेत्र में पुरुष कामगारों की संख्या बढ़ने लगी है, क्योंकि वे आसानी से कोठियों में चौबीस घंटे काम करने के लिए उपलब्ध होते है और ये चलन कोविड के बाद से ज़्यादा बढ़ा है, जिसकी वजह से महिला घरेलू कामगारों के रोज़गार के अवसर कम होने लगे है।

रूपाली ये भी बताती है कि, ‘कोविड से पहले कोठियों में घरेलू कामगार होने की वजह से भेदभाव होता था, लेकिन काम करने वालों की जाति नहीं पूछी जाती थी। लेकिन अब अगर काम खोजने जाओ तो पहले जाति पूछी जाती है।

कहाँ रहती हो? किस जाति की हो? जैसे सवाल अब अक्सर घरेलू कामगारों के सामने खड़े होते है। आगे शर्त होती है कि – ‘अगर बाथरूम साफ़ करेगी तो बर्तन नहीं धोएगी। ज़्यादा छुट्टी नहीं मिलेगी। वग़ैरह-वग़ैरह।‘ इस नाप-तौल के चक्कर में अब उन्हें काम नहीं मिलता है। कोविड के दौरान बढ़ी बेरोज़गारी की वजह से अब घरेलू कामगार महिलाएँ अपनी कोई भी बात नहीं रख सकती है, उन्हें हर शर्त और कीमत को मानकर काम करना पड़ता है। क्योंकि कोविड के बाद काम के मौक़े कम हो गए।

Illustration by Mrinalini Godara.

यूनियन से जुड़ाव और एक उम्मीद

कोविड दौरान रूपाली का जुड़ाव शहरी महिला कामगार यूनियन से हुआ। उस समय शहरों में कोविड के चलते साइबर कैफ़े जैसी सारी दुकाने बंद हो गयी थी और दूसरी तरफ़ सरकार की कल्याणकारी योजनाएँ ऑनलाइन हो गयी थी, जो मज़दूरों की पहुँच से बाहर थी। तब शहरी महिला कामगार यूनियन ने ज़न सूचना केंद्र के माध्यम से सरकारी योजनाओं से जोड़ने के लिए मज़दूरों के ऑनलाइन फार्म भरने व नाम चढ़वाने का काम शुरू किया। इसी दौरान रूपाली यूनियन की सदस्य गुड़िया से अपने राशन कार्ड में नाम चढ़वाने के लिए मिली। तभी से रूपाली का संगठन से जुड़ाव बना। उस समय रूपाली को यूनियन से दो से अधिक बार राशन मिला, जिस मदद से रूपाली बहुत खुश हुई। इसके बाद रूपाली संगठन से जुड़कर अपना योगदान राशन की लिस्ट बनवाने और महिलाओं को यूनियन से जोड़ने जैसे काम के ज़रिए देने लगी।

रूपाली के पति की कमाई क़र्ज़ उतारने और इलाज के खर्चे में चली जाती है। वहीं बीमारी की वजह से रूपाली को नए काम नहीं मिल पा रहे है, जिसके चलते उसे और उसके परिवार को बुरी तरह आर्थिक तंगी का शिकार होना पड़ रहा है। अपने मौलिक अधिकारों से वंचित सम्मानजनक ज़िंदगी से दूर रूपाली ने बचपन से जिस भेदभाव और संघर्ष को जिया है वो का भी लगातार क़ायम है। ऐसा लगता है मानो रूपाली एक जाल में फँस चुकी है, जहां चारों ओर समस्याएँ है। उसकी आवाज़ और मनोभावों से ऐसा लग रहा था जैसे पैंतीस साल की उम्र में वो बेबस और लाचार बुढ़ापा जीने को मजबूर है। लेकिन सबके बीच जब वो यूनियन में आती है तो उसके चेहरे पर एक अलग-सी चमक होती है। यहाँ वो अपना सुख-दुःख दूसरी महिलाओं से बाँटती है और दूसरी महिला कामगारों की मदद करती है, जो उसके चेहरे पर मुस्कान की वजह भी बन जाती है।

Domestic workers in India demand justice

Domestic workers in India are demanding justice and respect. Anita Kapoor, a founding member of the Shahri Mahila Kaamgar Union (SMKU – an unregistered union working with domestic workers in the Delhi-NCR region), shares the experiences and demands of domestic workers through their own words for International Domestic Workers’ Day.

We, the domestic workers, are on the margins of society due to the utter neglect of society and the Government. Our situation was further worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic and consequent lockdowns. We were swamped by death, illness, hunger and helplessness. We left our livelihoods in the cities. We walked thousands of kilometres to return to our villages on hungry stomachs. Where was the government then?

Domestic workers were accused of being carriers of the virus. Our employers began to look at us with eyes of hatred. Where was the government then?

In the name of the pandemic, we, women domestic workers, became unemployed and injustice was inflicted upon us. Where was the government then?

Who gave the police an open license to harass us on the streets when we were struggling with these worries?

The Covid-19 lockdowns ruined our lives

We worked hard to earn a livelihood and a life of dignity, but the pandemic pushed us to a situation of utter helplessness. Many domestic workers lost their livelihoods and income and had no idea when they would be reinstated. Not only did they not have monthly incomes, but they also lacked rations and health services due both to the lockdowns and to poorly designed support measures. This was the time that domestic workers and their households needed support the most, and yet we found that our appointed representatives did not extend their hands in support.

The methods used to deal with the pandemic perpetrated caste violence, economic, exploitation and religious atrocities. The education of children was wrecked. Bodies were flowing in rivers. There were long queues at cremation grounds and graveyards. There were oxygen shortages in hospitals. Large companies were given debt relief. The economy was in tatters. but crowds for elections were exempted. People were permitted to join the Kumbh Mela. The courts and systems of justice were closed. Instead of the parliamentarians being open to hearing people’s issues, parliamentary sessions were cut short and anti-people farmers’ laws and labour laws were passed. The regime was absent.

Our employers exploited our vulnerability during the Covid-19 pandemic to decrease wages and convert our working status to full-time live-in workers. For us, it was not the Covid-19 virus that was the problem, but the violence inflicted on us by our employers – the decrease in our wages, the non-stop 24-hour workday, the hateful looks, the cruelty – these were our real struggles.

These have been lasting effects on domestic workers, undoing all the progress we made in the past decades. Previously, we had the power to voice our demands, even if it was only for four days of holiday and a 500 INR bonus during festivals. But the pandemic robbed us of even that limited bargaining power and the capacity to organise.

The issue of unemployment is rife in our sector. The demonetisation of the Indian currency in 2016, followed by the pandemic, has caused us to sink under the weight of indebtedness and economic burdens. Our husbands and even our children do not have secure employment. We feel the burden of running our households. As a result, we are not always in good physical or mental health.

Our demands

Given the situation and challenges faced by domestic workers, we have several demands for the Government. We demand appropriate wages, a day’s leave in a week, fixed hours of work in a day and the assurance of provident fund, pension, workers’ social security, etc. We demand a regulator for the employers so that the many atrocities and forms of violence against workers stop.

It is important for domestic workers to speak together about what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and about the issues that we continue to face to this day. It is important for us to document and investigate these issues and demand accountability from the government. In this work, we all have a collective responsibility. Across India, various organisations are conducting public hearings calling for accountability. Allied domestic workers’ unions must also join hands with the National Platform for Domestic Workers to put pressure on the government to concede our demands. We must investigate government policies by setting up public inquiry committees in different places. This is our fundamental constitutional duty. It is our responsibility to undertake. All the people of this country have to join in these efforts.

The voices of domestic workers proclaim:

“COVID is a symbol of the violence and atrocities against domestic workers”

“Respect, dignity, love and rest – this is our demand as workers”

“Pay us the right price for our work- this is our slogan as workers”

“Let us gain our rights as workers – this our demand as domestic workers”

“Domestic work is work! Recognise domestic workers as workers!”

“Fix minimum wages for domestic workers now!”

“Fix our hours of work now!”

“We are workers, not slaves!”

“On the issues of livelihoods, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“On the issue of domestic workers, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“We will ensure accountability for what happened with us!”

This blog was produced in collaboration with Countering Backlash partner, Gender at Work Consulting – India, and originally written in Hindi (translation provided by Sudarsana Kundu and Shraddha Chigateri).

भारत में घरेलू कामगार न्याय की मांग करते हैं

समाज और सरकार की उपेक्षा की वजह से हम घरेलू कामगार आज भी हाशिए पर रहने को मजबूर हैं। लेकिन कोरोना और लॉकडाउन हम घरेलू कामगारों के लिए बेबसी भरे एक बेहद चुनौतीपूर्ण समय के रूप में सामने आया।

इस कठिन समय में हम मौत, बीमारी, भुखमरी और लाचारी से जूझ रहे थे और शहरों में अपनी मजदूरी छोड़कर जब भूखे पेट हजारों मील पैदल चलकर अपने गांव वापस आ रहे थे तो सरकार कही नहीं थी ?

इस महामारी के दौर में जब हमारी छोटी-सी आजीविका भी चली गई और काम कराने वाले लोग हमें घृणा की नजरों से देखने लगे तो भी सरकार कही नहीं थी?

घरेलू कामगार को कोरोना के वाहक बोलकर, कई कामगारों का काम, आमदनी ख़त्म कर दी गयी और उनके ख़िलाफ़ नफ़रत फैलायी जा रही थी उस समय सरकार कहाँ थी?

एक तरफ हम इन समस्याओं से जूझ रहे थे तो दूसरी तरफ सरकार ने सड़कों पर हमें परेशान करने के लिए पुलिस को खुली छूट दे रखी थी।

कोरोना महामारी के दौरान घरेलू कामगारों की मुसीबत और लाचारी सबसे ज़्यादा सामने आई। घरेलू कामगार महिलाओं को कोरोना महामारी के बहाने बेरोजगार करने, हमारी रोज़ी-रोटी का साधन छीनने जैसे अन्याय करने का काम हुआ।

महामारी के नामपर घरेलू कामगारों को काम से निकाल दिया गया। लेकिन उन्हें वापस काम में कब बुलाया जाएगा इसका किसी कामगार को इसका कोई अंदाज़ा नहीं था। उनके हाथ मासिक वेतन नहीं पहुँचा और इसके साथ ही राशन और स्वास्थ्य सुविधाओं का अभाव भी रहा। आमतौर पर यह समाज का वो तबका था, जो अपना श्रम देकर सम्मानपूर्वक जीवन गुजर बसर करता था। पर इस महामारी ने उनको भीख मांगने जैसे माहौल में लाकर खड़ा कर दिया। जब घरेलू कामगारों को ज़िम्मेदारी ज़न-प्रतिनिधियों की सबसे ज़्यादा ज़रूरत थी पर किसी ने भी इस तबके की तरफ़ मदद का हाथ आगे नहीं बढ़ाया।

बच्चों की शिक्षा ध्वस्त हो गई। नदियों में लाश बहती रही, श्मशान घाटों एवं कब्रिस्तानों पर लंबी कतारें, अस्पतालों में ऑक्सीजन की कमी, संसद सत्र में कटौती व संसद में लोगों की समस्याओं पर चर्चा के बजाय श्रमिक और जन-विरोधी कानूनों का पास होने का सिलसिला चलता रहा। एक ओर तो, देश की अर्थव्यवस्था का धराशाही होना, नदारद प्रशासन, बंद कोर्ट कचहरी एवं लोगों के प्रतिरोध पर तालाबंदी जैसी समस्याएँ हैं। वहीं दूसरी ओर, चुनाव में भीड़ के लिए छूट, कुंभ में जाने की छूट, सरकारी संस्थानों की बिक्री एवं पूंजीवादी बड़ी कंपनियों की कर्जमाफी जैसे मुद्दे हैं, जिनसे जनता जूझती रही।

इन सबके बीच वो घरेलू कामगार जो किन्हीं कारणवश शहर में बच गए थे, उनकी आजीविका की मजबूरी को समाज के संभ्रांत तबके (कोठी वाले) ने ‘आपदा में अवसर’ मानकर पूरा फायदा उठाया। उनमें से कई घरेलू कामगारों को कोठी वालों के घर में रहकर बिना रुके 24 घंटों तक काम करना पड़ा। उनकी मजदूरी बढ़ने की बजाय और कम होती गई। कोरोना महामारी के दौर में ऐसे शोषण बहुत से घरेलू कामगार लोगों के लिए असहनीय था। इनके लिए कोरोना समस्या नहीं थी, बल्कि कोठी वालों का अत्याचार, मजदूरी में कटौती, दिन-रात बिना रुके काम करवाना, घृणित निगाहें एवं क्रूरता इत्यादि समस्याएं थी।

आज भी घरेलू कामगारों की स्थिति पहले से बदतर है। बेरोज़गारी की स्थिति आज भी जस की तस बनी हुई है, जिससे हम अपनी जिंदगी के करीब 20 साल पीछे ही गए है। वे घरेलू कामगार, जिन्हें ‘चार छुट्टी या दिवाली पर 500 रुपए ही बोनस चाहिए।‘ – यह बोलकर लेने का हक मिला था, उस हक़ को इस महामारी ने छीन लिया। उनकी मोलभाव करने एवं अपने काम के अनुसार मज़दूरी की बात रखने की शक्ति एवं संगठनात्मिक शक्ति भी कम हुई है।

2016 में नोटबंदी हुईं इसके बाद साल 2020 में कोरोना महामारी ने घरेलू कामगारों की ऐसी कमर तोड़ी कि वे आज भी इससे उभर नहीं पा रहे है। वे आज भी आर्थिक बोझ के नीचे दबे हुए है । आज युवा बच्चों या पतियों का नियमित काम नहीं है। घर चलाने का बोझ परिवार घरेलू कामगारों पर आ गया है, जो उनके शारीरिक एवं मानसिक स्वास्थ्य को भी प्रभावित कर रही है।

घरेलू कामगारों के सामने आने वाली स्थिति और चुनौतियों को देखते हुए हमारी कई मांगें हैं। हम उचित वेतन, सप्ताह में एक दिन की छुट्टी, एक दिन में काम के निश्चित घंटे और भविष्य निधि, पेंशन, श्रमिकों की सामाजिक सुरक्षा आदि के आश्वासन की मांग करते हैं। घरेलू कामगारों के लिए एक नियामक हो जिससे कामगारों के साथ होने वाले अनेकों तरह के शोषण और अत्याचार पर रोक लगायी जा सके।

इसलिए घरेलू कामगारों के लिए यह जरूरी हो गया है कि, कोरोना लॉक डाउन के समय आज की परिस्थितियों में जिन समस्याओं का सामना करना पड़ रहा है। उन्हें एक साथ कहना, उनकी जांच करना और समस्याओं को दस्तावेज में तब्दील करके सरकार की जवाबदेही तय करना अनिवार्य है। इस कार्य में सभी की सामूहिक भूमिका अहम है। देश के कोने-कोने से विभिन्न संगठन इस तरह की जनसुनवाई कर रहे हैं। ऐसी स्थिति में सहयोगी संगठन के साथ मिलकर घरेलू कामगारों के लिए राष्ट्रीय मंच ( NPDW) को भी अपनी बात मनवाने के लिए सरकार पर दबाव डालना चाहिए। जगह-जगह सार्वजनिक जांच समितियां बनाकर सरकार की नीतियों की जांच करनी चाहिए। यह जांच संविधान के तहत हमारा मौलिक कर्तव्य है, जिसे करना हमारी जिम्मेदारी है । देश के सभी लोगों को एक साथ मिलकर यह काम करना चाहिए।

घरेलू कामगारों की आवाज़ें