The Brazilian press has drawn attention to the dismantling and removal of women’s and other vulnerable groups’ rights in the country recently, especially during the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro between 2019 to 2023.

There are many issues that encompass violence against women, by individuals and by the Brazilian State, much of which is now having to be re-addressed under the government of Lula. The criminalisation of abortion and violence against women activists – or those in political positions – have been a focus of the press, especially in recent times. The activities of feminist, black, indigenous and LGBTQIA+ movements have also elicited strong reactions from conservative forces.

There is, however, a concern about the way the press has constructed their news about this, the way in which it is framed, and which subjects are in the spotlight.

NEIM has produced a new toolkit as part of the Countering Backlash programme specifically for journalists and communications professionals. It emerged to tackle media coverage of gender-based political violence and reproductive rights in Brazil. Here are five ways the toolkit can be used for responsible media coverage.

1) Pay attention to what is on the agenda

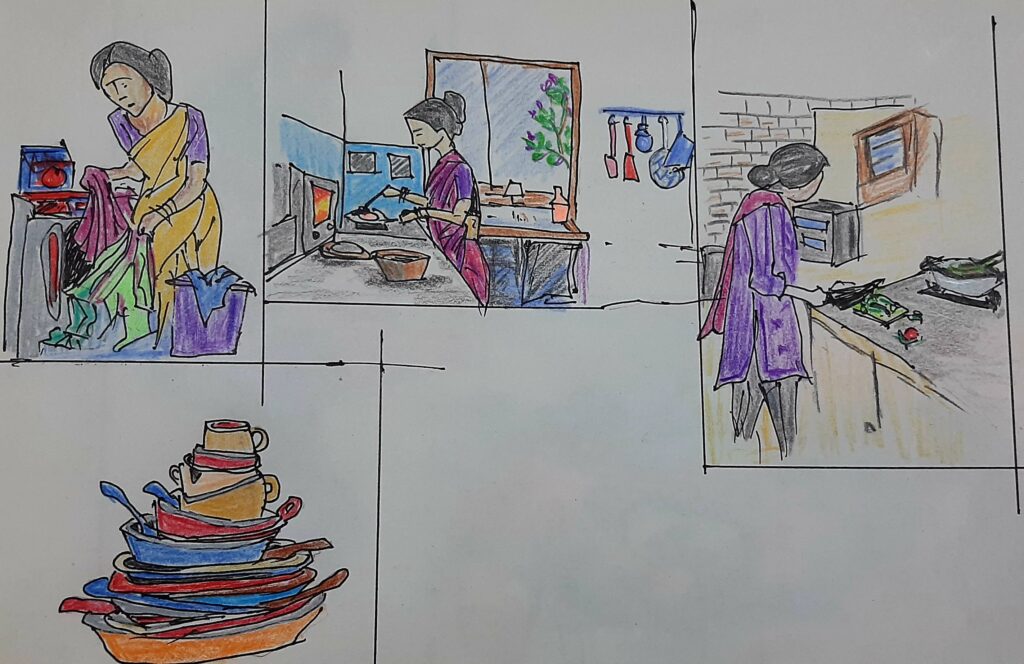

Media outlets have an agenda, often politicised, for the construction of their news. However, it is not always possible to create a strategic and detailed agenda, particularly when a ‘hot topic’ suddenly comes into the news, without the opportunity for a good investigation. However, this should not mean that the agenda cannot have a humanised approach to women’s lives and rights.

For journalists, this means paying close attention to the choice of sources, framing, and how we approach the topics. On one hand, abortion, although in some cases illegal in Brazil, is a public health issue. On the other hand, the coverage of women with political representation should be about their actions, not their bodies. Journalists and those working in news media should always choose not to re-victimise and/or criminalise women who are fighting for their rights or whose decisions over their bodies are prohibited.

2) Enquire about the topic you are covering

Ask yourself, what are the best ways to communicate about sensitive and potentially controversial topics? The persecution of those who seek and obtain abortions granted by law and or who face political gender violence is frequent in Brazil.

The ‘facts’ are not isolated. Always enquire about previous events as well as gender issues. In our toolkit, we conceptually address gender-based political violence and reproductive rights, as well as breaking them down.

3) Pay attention to the language used

It is important to know the main terms and understand the best way to talk about and approach topics that can be distressing for some people. Whenever possible, choose to add a content warning to your article or report. In the toolkit, we explain the most suitable concepts and terms to deal with gender-based political violence and reproductive rights. This will help to pass on crucial methods and information for countering backlash and contribute to creating knowledge and empathy on the subject.

A key, and important, example of this is that people who have abortions are not only cisgender women but also trans men and non-binary people, so avoid using the word ‘women’. When applicable, use the expression ‘people who menstruate’ or ‘people who get pregnant’. Clothing, hair, body shape: none of this is news. Coverage of people with political representation should be about their actions, not their bodies.

4) Contact trustworthy sources in the field

In the toolkit, you will have access to some reporting channels and reliable sources with information on gender-based political violence and reproductive rights. It is extremely important to check them before publishing your materials, as well as making periodic updates, particularly if these are topics that you often deal with. When in doubt, always question, and don’t hesitate to ask experts for help or clarification.

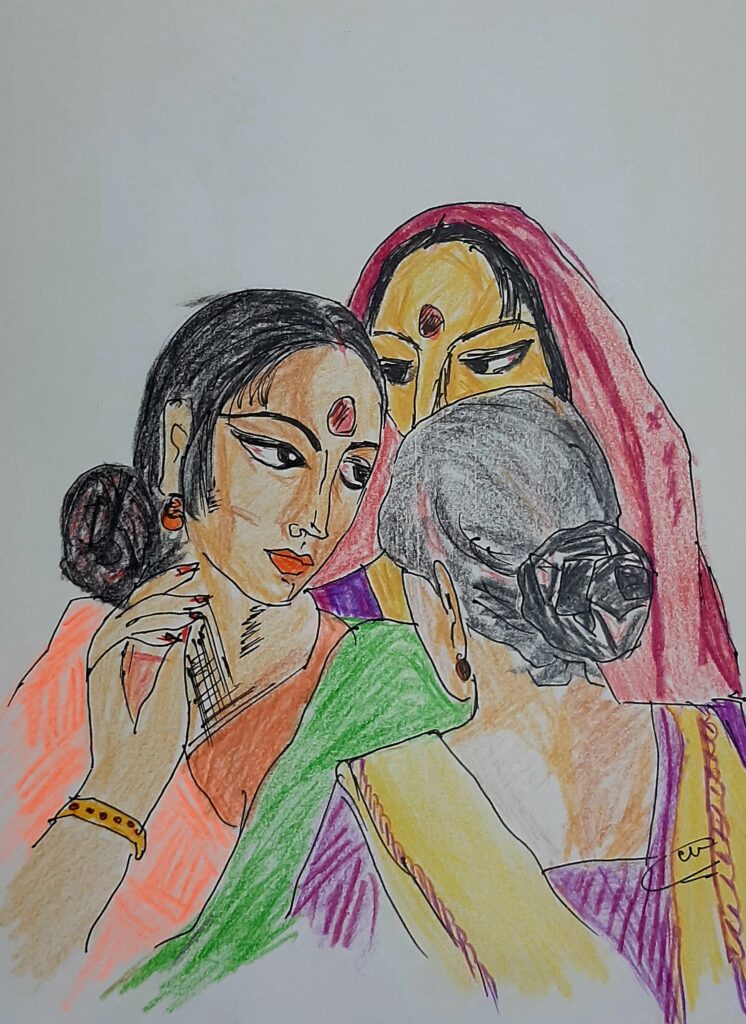

If one of your sources is a person who suffers political gender violence or who has had an abortion, guard them and protect their identities. Those who experience political gender violence may be at constant risk and, due to the illegality of most abortions, the protection of their identities is essential. Do not share their names, images, voice, location, or any other potentially identifiable features, and consider doing so even when you have been given permission.

5) Beware of the risk of re-victimisation

The exposure of victims’ identities should never be done, and their anonymity and privacy must be valued at all times when broadcasting news about it. When we talk about issues that are related, directly or indirectly, to violence – such as political gender violence and reproductive rights – especially related to groups that are already vulnerable, we must be extra careful with how we refer to the victims.

Do not exploit their suffering; the news should never be prioritised in favour of unnecessary exposure to the person who has suffered some type of violence, neglect or abuse.