This research report from the Arab Institute for Women explores the presence of backlash in Lebanese media, and how it is used. […]

Understanding Backlash in Lebanon

This research report from the Arab Institute for Women explores definitions of backlash, and how backlash should be understood in Lebanon. […]

Chess for Countering Backlash

This Chess – Shatranj or Chaturanga – workshop exercise can be played in various ways. You can play this as an exercise – or a series of exercises – in a workshop setting. You can also do it at home or at your desk, to aid thinking and research. […]

Understanding gender backlash through Southern perspectives

Global progress on gender justice is under threat. We are living in an age where major political and social shifts are resulting in new forces that are visibly pushing back to reverse the many gains made for women’s and LGBTQ+ rights and to shrink civic space.

The focus of this year’s UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) calls for ‘accelerating the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls…’. This ‘acceleration’ would be welcome indeed. We are not so much worried about slow progress but rather by the regress in a tidal wave of patriarchal – or gender – backlash, with major rollbacks of earlier advances for women’s equality and rights, as well as by a plethora of attacks on feminist, social justice and LGBTQ+ activists, civic space and vulnerable groups of many stripes.

The Countering Backlash programme explores this backlash against rights in a timely and important IDS Bulletin titled ‘Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives’. In it, we ask ‘how can we better understand the contemporary swell of anti-feminist (or patriarchal) backlash across diverse settings?’. We present a range of perspectives and emerging evidence from our programme partners from Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Kenya, Lebanon, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.

Here’s what you can find in our special issue of the IDS Bulletin.

Why we need to understand gender backlash

‘Anti-gender backlash’, at its simplest, it refers to strong negative reactions against gender justice and those seeking it. Two widely known contemporary examples, from different contexts, are Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill (passed in 2023), and the United States Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe vs Wade (which gave women the constitutional right to abortion) in 2022.

The term ‘backlash’ was first used in Susan Faludi’s (1991) analysis of the pushback against feminist ideas in 1980s in the United States, and historically, understandings of anti-gender backlash have been predominantly based on experiences and theorising about developments in the global north. More recent scholarship has afforded insights on and from Latin America and Eastern Europe.

Much explanatory work to date, if it does not implicitly generalise from global north experience, often fails to adequately engage with the ways these locally specific phenomena operate transnationally, including across the global south, and with its complex imbrication in a broader dismantling of democracy.

New ways of analysing gender backlash

The Issue presents new ways of analysing backlash relevant to diverse development contexts, grounded examples, and evidence of anti-gender dynamics. It aims to push this topic out of the ‘gender corner’ to connect it to contemporary shifts in relationships between faith, identity and state, governance, and the broader politics of democracy and economics, as seen from across the global south.

The articles in this special issue are grouped into three themes: one, on ‘voice and tactics’, including whose voices are being heard, and what tactics are being used?; two, on ‘framings and direction’, including how are ideologies spread, and how can we understand attitudes to change? and; three, on ‘temporality and structure’, including what is ‘back’ about backlash? What and who drives it, and how is it imbricated in broader trends and crises? Additionally, most articles proffer some thoughts and recommendations on the implications for directions to counter backlash, whether specifically for feminist movements, for other gender and social justice defenders, or for researchers and students.

Southern Perspectives

This Issue fundamentally challenges simple and reductive understandings of gender backlash. Diverse examples of politicised backlash are ‘mapped’ across geographies and viewpoints. This can help to build a more granular and multi-perspectival understanding of backlash, of its more subtle processes of co-optation and division, its connected across borders, regions, and continents, and the contextual and different strategies of resistance.

Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives

The 30th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995, and the 10th anniversary of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are fast approaching. And with global progress on gender justice on the rise around the world, we must find ways to combat gender backlash now.

The Countering Backlash programme has produced timely research and analysis on gender backlash, presenting a range of perspectives and emerging evidence on backlash against gender justice and equality, as such phenomena manifest locally, nationally, and internationally.

‘Understanding Gender Backlash: Southern Perspectives’ is our iteration of the IDS Bulletin, including contributions, insights, expert knowledge from a range of actors in diverse locations across South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, Lebanon and the UK – and all part of the Countering Backlash programme.

The IDS Bulletin addresses the urgent question of how we can better understand the recent swell of anti-gender backlash across different regions, exploring different types of actors, interests, narratives, and tactics for backlash in different places, policy areas, and processes.

The IDS Bulletin will be launched by a hybrid event on 07 March 2024, ahead of the programme’s attendance at UN Women’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) 2024.

Articles

Jerker Edström; Jennifer Edwards; Chloe Skinner; Tessa Lewin; Sohela Nazneen

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Sohela Nazneen

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Cecília Sardenberg; Teresa Sacchet; Maíra Kubík Mano; Luire Campelo; Camila Daltro; Talita Melgaço Fernandes; Heloisa Bandeira;

Nucleus of Interdisciplinary Women’s Studies of the Federal University of Bahia (NEIM)

Maheen Sultan; Pragyna Mahpara

BRAC BIGD

Adeepto Intisar Ahmed; Ishrat Jahan; Israr Hasan; Sabina Faiz Rashid; Sharin Shajahan Naomi

BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health

Jerker Edström

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Abhijit Das; Jashodhara Dasgupta; Maitrayee Mukhopadhyay; Sana Contractor; Satish Kumar Singh

Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ)

Shraddha Chigateri; Sudarsana Kundu

Gender at Work Consulting – India

Phil Erick Otieno; Alfred Makabira

Advocates for Social Change Kenya (ADSOCK)

Amon A. Mwiine; Josephine Ahikire

Centre for Basic Research

Tessa Lewin

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Nay El Rahi; Fatima Antar

Arab Institute for Women (AIW)

Jerker Edström, Jenny Edwards, Tessa Lewin, Rosie McGee, Sohela Nazneen, Chloe Skinner

Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Event: Sustaining and expanding south-south-north partnerships and knowledge co-construction on global backlash to reclaim gender justice

We are living in a time of global unrest and division stoked by increasing polarisation in politics, authoritarianism and backlash on gender equality, inclusion and social justice.

This event, during the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) 2024, explored how effective south-south-north partnerships can develop better and more nuanced understandings of gender backlash, to inform strategies for defending gender justice.

Based on research from the Countering Backlash programme, this event was a discussion between researchers, civil society activists, with bi- and multi-lateral development agencies. It provided insights from research and policy spaces on how we can work together more effectively to reclaim gender justice.

Starting in a panel format, speakers were asked to reflect on key insights from partnering in research on backlash, in activism and in international policy spheres. The co-chairs facilitated a dialogue between panellists and then opened up the discussion with the audience.

This event was hosted by the Lebanese American University, and co-sponsored by the Government of Sweden.

When

- 13 March 2024

- 12:00-14:00 EST // 16:00 – 18:00 UK Time

Where

- In person – Lebanese American University, New York

- Online – WebEx

Speakers

- Nay El Rahi, Activist and Researcher, Arab Institute for Women, Lebanese American University

- Phil Otieno, Executive Director, Advocates for Social Change Kenya (ADSOCK)

- Tessa Lewin, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

- Jerker Edström, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

- Ida Petterson, SIDA – Sweden

- Karen Burbach, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands

- Constanza Tabbush, Research Specialist, UN Women

Co-chairs

- Myriam Sfeir – Arab Institute for Women, Lebanese American University

- Sohela Nazneen – Institute of Development Studies

Event: How is backlash weakening institutional contexts for gender justice globally?

Gender backlash is continually gaining momentum across the globe, and social and political institutions and policies are being dismantled. Gender justice activists and women’s rights organisations are having to mobilise quickly to counter these attacks.

With speakers from Bangladesh, Uganda, Lebanon, Serbia and India, in this official NGO CSW68 event we asked, ‘how is gender backlash weakening institutional contexts for gender justice globally?’ Speakers discussed: stalling and lack of implementation of the Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Act (2010) in Bangladesh; the infiltration of conservative religious and political actors in democratic institutions in the context of Serbia and neighbouring countries; anti-feminist backlash as institutional by default in Lebanon; and the legislative weakening of institutional contexts in Uganda, examining Acts which exert control over Civil Society Organisations.

When

- 11 March 2024

Speakers

- Pragyna Mahpara, BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD)

- Sandra Aceng, Executive Director, Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET)

- Nay El Rahi, Activist and Researcher, Arab Institute for Women (AIW)

- Nađa Bobičić, Researcher, Center for Women’s Studies Belgrade (CWS)

- Santosh Kumar Giri, Director, Kolkata Rista

-

Jerker Edström, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

Chair

- Chloe Skinner, Research Fellow, IDS

Podcast: Politicising masculinity and its politics in the global context

Event: Counting the cost: funding flows, gender backlash and counter backlash

Major political and social shifts are stifling the possibility of gender justice across the world. Analysing this backlash as operating on global, regional and local scales in this webinar, we ask, where is the money?

While predominant anti-gender backlash movements and actors appear well financed, those countering backlash face significant financial challenges, heightened in the context of rising authoritarianism and shrinking civic space.

In this event, we were joined by leading experts and partners from Countering Backlash and beyond. Isabel Marler from the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) presented a mapping of sources of funding for anti-rights actors, and interrogate what is effective in countering anti-rights trends, while Lisa VeneKlasen (Independent Strategist, Founder and Former Executive Director of JASS), explored ‘where is philanthropy on anti-gender backlash’? Turning to national restrictions, Sudarsana Kundu and Arundhati Sridhar from our partner organisation Gender at Work Consulting – India focused on the impacts of funding laws for women’s rights organising in India.

When

- 12 December 2023

- 13:00 – 14:30 UK time

Speakers

- Lisa VeneKlassen, Independent Strategist, Founder and Former Executive Director of JASS (Just Associates)

- Isabel Marler, Lead, Advancing Universal Rights and Justice, Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID)

- Sudarsana Kundu, Executive Director, Gender at Work Consulting – India

- Arundhati Sridhar, Gender at Work Consulting – India

Discussant

- Rosie McGee, Research Fellow, IDS

Chair

- Chloe Skinner, Research Fellow, IDS

Watch the recording

Patriarchal (Dis)orders: Backlash as Crisis Management

This article examines more global dynamics of backlash, exploring the question of why and how it has emerged with greater intensity in recent years, and how we can better understand it. […]

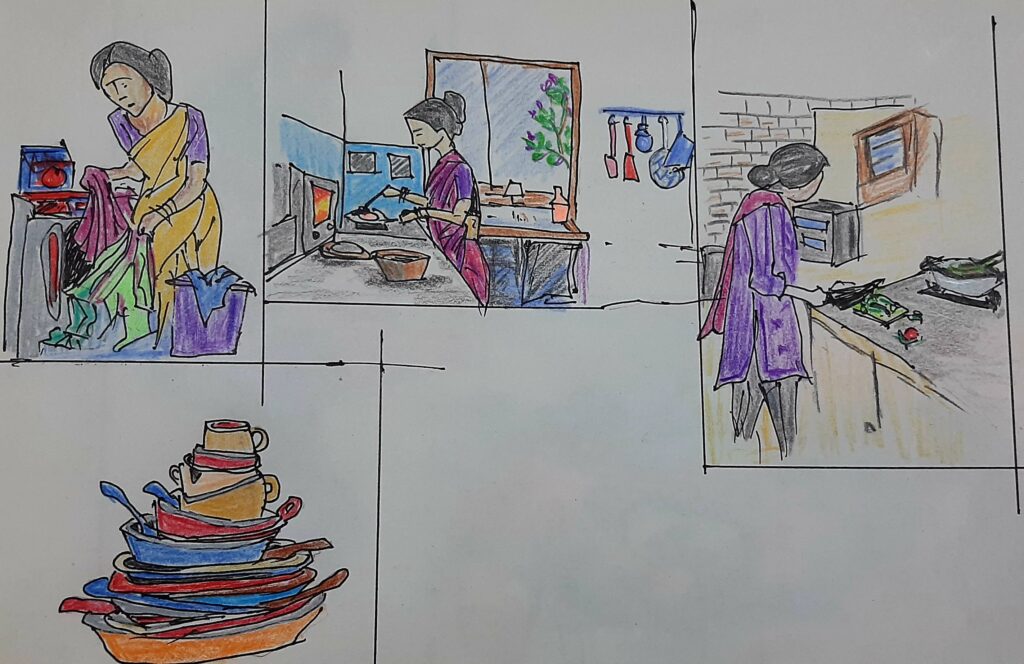

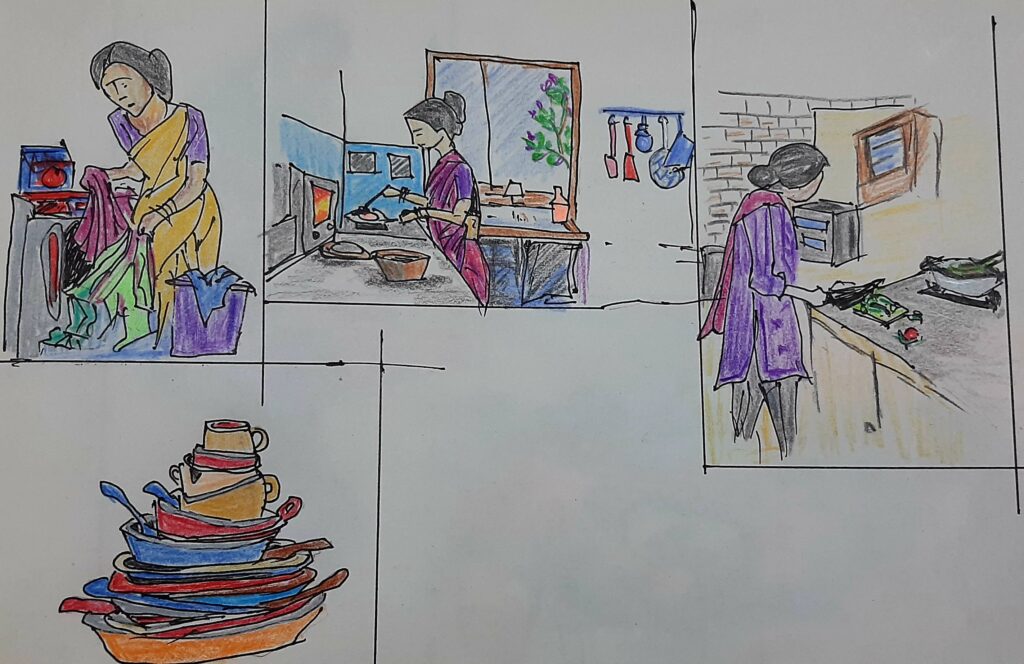

Domestic workers in India demand justice

Domestic workers in India are demanding justice and respect. Anita Kapoor, a founding member of the Shahri Mahila Kaamgar Union (SMKU – an unregistered union working with domestic workers in the Delhi-NCR region), shares the experiences and demands of domestic workers through their own words for International Domestic Workers’ Day.

We, the domestic workers, are on the margins of society due to the utter neglect of society and the Government. Our situation was further worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic and consequent lockdowns. We were swamped by death, illness, hunger and helplessness. We left our livelihoods in the cities. We walked thousands of kilometres to return to our villages on hungry stomachs. Where was the government then?

Domestic workers were accused of being carriers of the virus. Our employers began to look at us with eyes of hatred. Where was the government then?

In the name of the pandemic, we, women domestic workers, became unemployed and injustice was inflicted upon us. Where was the government then?

Who gave the police an open license to harass us on the streets when we were struggling with these worries?

The Covid-19 lockdowns ruined our lives

We worked hard to earn a livelihood and a life of dignity, but the pandemic pushed us to a situation of utter helplessness. Many domestic workers lost their livelihoods and income and had no idea when they would be reinstated. Not only did they not have monthly incomes, but they also lacked rations and health services due both to the lockdowns and to poorly designed support measures. This was the time that domestic workers and their households needed support the most, and yet we found that our appointed representatives did not extend their hands in support.

The methods used to deal with the pandemic perpetrated caste violence, economic, exploitation and religious atrocities. The education of children was wrecked. Bodies were flowing in rivers. There were long queues at cremation grounds and graveyards. There were oxygen shortages in hospitals. Large companies were given debt relief. The economy was in tatters. but crowds for elections were exempted. People were permitted to join the Kumbh Mela. The courts and systems of justice were closed. Instead of the parliamentarians being open to hearing people’s issues, parliamentary sessions were cut short and anti-people farmers’ laws and labour laws were passed. The regime was absent.

Our employers exploited our vulnerability during the Covid-19 pandemic to decrease wages and convert our working status to full-time live-in workers. For us, it was not the Covid-19 virus that was the problem, but the violence inflicted on us by our employers – the decrease in our wages, the non-stop 24-hour workday, the hateful looks, the cruelty – these were our real struggles.

These have been lasting effects on domestic workers, undoing all the progress we made in the past decades. Previously, we had the power to voice our demands, even if it was only for four days of holiday and a 500 INR bonus during festivals. But the pandemic robbed us of even that limited bargaining power and the capacity to organise.

The issue of unemployment is rife in our sector. The demonetisation of the Indian currency in 2016, followed by the pandemic, has caused us to sink under the weight of indebtedness and economic burdens. Our husbands and even our children do not have secure employment. We feel the burden of running our households. As a result, we are not always in good physical or mental health.

Our demands

Given the situation and challenges faced by domestic workers, we have several demands for the Government. We demand appropriate wages, a day’s leave in a week, fixed hours of work in a day and the assurance of provident fund, pension, workers’ social security, etc. We demand a regulator for the employers so that the many atrocities and forms of violence against workers stop.

It is important for domestic workers to speak together about what happened during the Covid-19 pandemic and about the issues that we continue to face to this day. It is important for us to document and investigate these issues and demand accountability from the government. In this work, we all have a collective responsibility. Across India, various organisations are conducting public hearings calling for accountability. Allied domestic workers’ unions must also join hands with the National Platform for Domestic Workers to put pressure on the government to concede our demands. We must investigate government policies by setting up public inquiry committees in different places. This is our fundamental constitutional duty. It is our responsibility to undertake. All the people of this country have to join in these efforts.

The voices of domestic workers proclaim:

“COVID is a symbol of the violence and atrocities against domestic workers”

“Respect, dignity, love and rest – this is our demand as workers”

“Pay us the right price for our work- this is our slogan as workers”

“Let us gain our rights as workers – this our demand as domestic workers”

“Domestic work is work! Recognise domestic workers as workers!”

“Fix minimum wages for domestic workers now!”

“Fix our hours of work now!”

“We are workers, not slaves!”

“On the issues of livelihoods, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“On the issue of domestic workers, the government will be investigated by us/ its own citizens”

“We will ensure accountability for what happened with us!”

This blog was produced in collaboration with Countering Backlash partner, Gender at Work Consulting – India, and originally written in Hindi (translation provided by Sudarsana Kundu and Shraddha Chigateri).

भारत में घरेलू कामगार न्याय की मांग करते हैं

समाज और सरकार की उपेक्षा की वजह से हम घरेलू कामगार आज भी हाशिए पर रहने को मजबूर हैं। लेकिन कोरोना और लॉकडाउन हम घरेलू कामगारों के लिए बेबसी भरे एक बेहद चुनौतीपूर्ण समय के रूप में सामने आया।

इस कठिन समय में हम मौत, बीमारी, भुखमरी और लाचारी से जूझ रहे थे और शहरों में अपनी मजदूरी छोड़कर जब भूखे पेट हजारों मील पैदल चलकर अपने गांव वापस आ रहे थे तो सरकार कही नहीं थी ?

इस महामारी के दौर में जब हमारी छोटी-सी आजीविका भी चली गई और काम कराने वाले लोग हमें घृणा की नजरों से देखने लगे तो भी सरकार कही नहीं थी?

घरेलू कामगार को कोरोना के वाहक बोलकर, कई कामगारों का काम, आमदनी ख़त्म कर दी गयी और उनके ख़िलाफ़ नफ़रत फैलायी जा रही थी उस समय सरकार कहाँ थी?

एक तरफ हम इन समस्याओं से जूझ रहे थे तो दूसरी तरफ सरकार ने सड़कों पर हमें परेशान करने के लिए पुलिस को खुली छूट दे रखी थी।

कोरोना महामारी के दौरान घरेलू कामगारों की मुसीबत और लाचारी सबसे ज़्यादा सामने आई। घरेलू कामगार महिलाओं को कोरोना महामारी के बहाने बेरोजगार करने, हमारी रोज़ी-रोटी का साधन छीनने जैसे अन्याय करने का काम हुआ।

महामारी के नामपर घरेलू कामगारों को काम से निकाल दिया गया। लेकिन उन्हें वापस काम में कब बुलाया जाएगा इसका किसी कामगार को इसका कोई अंदाज़ा नहीं था। उनके हाथ मासिक वेतन नहीं पहुँचा और इसके साथ ही राशन और स्वास्थ्य सुविधाओं का अभाव भी रहा। आमतौर पर यह समाज का वो तबका था, जो अपना श्रम देकर सम्मानपूर्वक जीवन गुजर बसर करता था। पर इस महामारी ने उनको भीख मांगने जैसे माहौल में लाकर खड़ा कर दिया। जब घरेलू कामगारों को ज़िम्मेदारी ज़न-प्रतिनिधियों की सबसे ज़्यादा ज़रूरत थी पर किसी ने भी इस तबके की तरफ़ मदद का हाथ आगे नहीं बढ़ाया।

बच्चों की शिक्षा ध्वस्त हो गई। नदियों में लाश बहती रही, श्मशान घाटों एवं कब्रिस्तानों पर लंबी कतारें, अस्पतालों में ऑक्सीजन की कमी, संसद सत्र में कटौती व संसद में लोगों की समस्याओं पर चर्चा के बजाय श्रमिक और जन-विरोधी कानूनों का पास होने का सिलसिला चलता रहा। एक ओर तो, देश की अर्थव्यवस्था का धराशाही होना, नदारद प्रशासन, बंद कोर्ट कचहरी एवं लोगों के प्रतिरोध पर तालाबंदी जैसी समस्याएँ हैं। वहीं दूसरी ओर, चुनाव में भीड़ के लिए छूट, कुंभ में जाने की छूट, सरकारी संस्थानों की बिक्री एवं पूंजीवादी बड़ी कंपनियों की कर्जमाफी जैसे मुद्दे हैं, जिनसे जनता जूझती रही।

इन सबके बीच वो घरेलू कामगार जो किन्हीं कारणवश शहर में बच गए थे, उनकी आजीविका की मजबूरी को समाज के संभ्रांत तबके (कोठी वाले) ने ‘आपदा में अवसर’ मानकर पूरा फायदा उठाया। उनमें से कई घरेलू कामगारों को कोठी वालों के घर में रहकर बिना रुके 24 घंटों तक काम करना पड़ा। उनकी मजदूरी बढ़ने की बजाय और कम होती गई। कोरोना महामारी के दौर में ऐसे शोषण बहुत से घरेलू कामगार लोगों के लिए असहनीय था। इनके लिए कोरोना समस्या नहीं थी, बल्कि कोठी वालों का अत्याचार, मजदूरी में कटौती, दिन-रात बिना रुके काम करवाना, घृणित निगाहें एवं क्रूरता इत्यादि समस्याएं थी।

आज भी घरेलू कामगारों की स्थिति पहले से बदतर है। बेरोज़गारी की स्थिति आज भी जस की तस बनी हुई है, जिससे हम अपनी जिंदगी के करीब 20 साल पीछे ही गए है। वे घरेलू कामगार, जिन्हें ‘चार छुट्टी या दिवाली पर 500 रुपए ही बोनस चाहिए।‘ – यह बोलकर लेने का हक मिला था, उस हक़ को इस महामारी ने छीन लिया। उनकी मोलभाव करने एवं अपने काम के अनुसार मज़दूरी की बात रखने की शक्ति एवं संगठनात्मिक शक्ति भी कम हुई है।

2016 में नोटबंदी हुईं इसके बाद साल 2020 में कोरोना महामारी ने घरेलू कामगारों की ऐसी कमर तोड़ी कि वे आज भी इससे उभर नहीं पा रहे है। वे आज भी आर्थिक बोझ के नीचे दबे हुए है । आज युवा बच्चों या पतियों का नियमित काम नहीं है। घर चलाने का बोझ परिवार घरेलू कामगारों पर आ गया है, जो उनके शारीरिक एवं मानसिक स्वास्थ्य को भी प्रभावित कर रही है।

घरेलू कामगारों के सामने आने वाली स्थिति और चुनौतियों को देखते हुए हमारी कई मांगें हैं। हम उचित वेतन, सप्ताह में एक दिन की छुट्टी, एक दिन में काम के निश्चित घंटे और भविष्य निधि, पेंशन, श्रमिकों की सामाजिक सुरक्षा आदि के आश्वासन की मांग करते हैं। घरेलू कामगारों के लिए एक नियामक हो जिससे कामगारों के साथ होने वाले अनेकों तरह के शोषण और अत्याचार पर रोक लगायी जा सके।

इसलिए घरेलू कामगारों के लिए यह जरूरी हो गया है कि, कोरोना लॉक डाउन के समय आज की परिस्थितियों में जिन समस्याओं का सामना करना पड़ रहा है। उन्हें एक साथ कहना, उनकी जांच करना और समस्याओं को दस्तावेज में तब्दील करके सरकार की जवाबदेही तय करना अनिवार्य है। इस कार्य में सभी की सामूहिक भूमिका अहम है। देश के कोने-कोने से विभिन्न संगठन इस तरह की जनसुनवाई कर रहे हैं। ऐसी स्थिति में सहयोगी संगठन के साथ मिलकर घरेलू कामगारों के लिए राष्ट्रीय मंच ( NPDW) को भी अपनी बात मनवाने के लिए सरकार पर दबाव डालना चाहिए। जगह-जगह सार्वजनिक जांच समितियां बनाकर सरकार की नीतियों की जांच करनी चाहिए। यह जांच संविधान के तहत हमारा मौलिक कर्तव्य है, जिसे करना हमारी जिम्मेदारी है । देश के सभी लोगों को एक साथ मिलकर यह काम करना चाहिए।

घरेलू कामगारों की आवाज़ें

“कोविड एक निशानी है, शोषण और अत्याचारों की”

“इज्जत, गरिमा, प्यार, आराम

हम कामगारों की यही है मांग”

“हम कामगारों का यही है नारा

कामों का दो दाम हमारा।”

“घरेलू कामगारों की यही पुकार

हमारे काम को मिले काम का सही अधिकार।“

“घरेलू काम भी एक काम है

हमें भी कामगार का दर्जा दो दर्जा दो”

” घरेलू कामगारों के मुद्दों पर, सरकार को अपनी जांचेंगे”

“आजीविका के मुद्दे पर, सरकार को अपनी जांचेंगे”

“घरेलू कामगारों का न्यूनतम वेतन तय करो, तय करो।”

” घरेलू कामगारों के काम के घंटे तय करो, तय करो”

“हम कामगार है, गुलाम नहीं”

” हमारे साथ जो हुआ उसका हिसाब हम करेंगे”

5 ways Serbia can #EmbraceEquity

Continuous normalisation of gender-based violence in the media in Serbia has led to women from all over the country coming together to fight for gender equality. Additionally, EuroPride, held in Belgrade in September 2022, received severe backlash from right-wing groups and ultimately had to be reorganised with a shorter route.

These events have exposed the limits of gender equality in Serbia, the strength of anti-gender organising, and the lack of support from the current government, who is pushing right-wing radicalisation via media outlets. With this in mind, here are five ways Serbia can better #EmbraceEquity:

1. Government control of the media must stop

The current Serbian political arena is dominated by right-wing, authoritarian beliefs that limit the space for alternative political views. This has transformed over time, as the ruling party’s control over state resources and the media has resulted in a constant increase of poverty and social divides. As public dissatisfaction is directed, with support of the ruling party, at the perceived Other/s, it has created an intolerance towards any diversity, including gender, in which the media play an important role.

Constant pressure on civil society organisations; threatened financial sustainability; and further fragmentation of the civil society sector is creating an increasingly difficult and dangerous environment for the work of feminist organisations. Thus, there is an increased need for observation of media coverage of gender equality issues and the rights of minority groups, as well as applying pressure on state institutions to react more quickly to media regulation violations.

2. There must be broader support of progressive independent media

In the face of the right-wing, conservative backlash against gender equality in Serbia, Centre for Women’s Studies latest media discourse research (publication forthcoming) has shown that the term ‘gender ideology’ is less prevalent than the term ‘family (and traditional) values’. This latter term has a great capacity for mobilising the Serbian population as it covers a wide range of meanings. Present in mainstream media, advocates for the fight against so called ‘gender ideology’ use the term ‘family values’ to defend the role of the ‘natural family’. In their view, the ‘natural family’ is under threat by various social and legislative interventions concerning reproductive and LGBTQIA+ rights, as well as measures against gender discrimination, equity for same-sex communities, sexual education, and protection from gender-based violence.

Against this backdrop, independent media outlets offer an inclusive, multi-perspective, gender-sensitive way of reporting, giving a voice to marginalised communities. These outlets are important to Serbian society for diversifying the debate and fighting against fake news. As such, it is necessary that different progressive actors – national and international independent journal associations, civil society among other – give support for progressive media in their work of defending freedom of speech and adhere to the highest standards of the journalistic profession.

3. More debate about the role of gender in Serbian society

The fight for gender justice in Serbia is receiving backlash from advocates of tradition on at least two levels: sexuality outside hetero norms; and gender roles and feminism. Heteronormativity is present every day in the mainstream media, particularly in the months preceding the Pride parades or when addressing the possibility of legal regulation for same-sex unions. At the centre of this conflict is the defence of the so-called ‘traditional family’ from the attack of progressive actors from the West.

Similarly, at the level of gender roles and feminism, the backlash from the anti-gender movement also relies on traditionalist views of the family structure, placing men and women within certain roles and hierarchies. As such, work must be done to widen the understanding of gender and its role as part of the radical right-wing political agenda through debate and knowledge exchange.

4. The local political context must be reanalysed

The Serbian media landscape is seeing increased influence from anti-gender advocates, from both Eastern and Western Europe, with some specificities that are primarily connected to the local political context.

The fight for gender justice is seen as an attack on local cultures by foreign powers. In Serbia, this is framed as destroying national sovereignty and the Serbian national identity. Furthermore, part of the local right-wing political and intellectual elite plays an active role in this framing, lending support to the narrative of an ‘attack on the national identity and family values’. The rejection of democratic values is also connected with the rise of Russia’s increased sphere of influence and the strengthening of conservative Orthodox ideas about the ‘traditional family’. A careful analysis of the local political context is required, which should be followed by a progressive media response.

5. Feminist organisations must mobilise

Relying on a biological understanding of gender and sexuality and insisting on a traditionalist family structure is part of a broader rejection of ideas and practices of social and human equality. In this sense, using the terms ‘gender ideology’, ‘family values’, and ‘traditional values’ in the media space in Serbia clearly corresponds to the wider action of the international anti-gender movement.

A response to the international organising of conservative actors should be formed at an international level and from a progressive perspective. Anti-gender ideas often find ways to cross borders, which is one reason why they prove to be influential and dangerous for the progress of human rights. The concept of ‘family values’ is the backbone of this discourse. International feminist and LGBTQIA+ solidarity organisations should find models to counter such ideas. The role of progressive independent media in the process of formulating different narratives, and in their marketing across national borders, is particularly significant.

Looking ahead

Over the past ten years, Serbia has seen a significant decline in democratic governance and free speech. The intensified attacks on gender equality and the rights of LGBTQIA+ persons, as well on NGOs and civil society, is part of this oppression. Despite this, resistance to these processes exists and will continue to exist. The fight for gender equality in Serbia remains an important part of the wider fight for a fairer society in which there will be no gender inequality, but also national, religious, political and any other oppression and exploitation.

A longer version of this blog can be found on the Centre for Women’s Studies website.

Who wins when human rights are set against each other?

Activists and development practitioners have historically used human rights to advocate for changes in law and policy to protect the rights of vulnerable communities or groups. More recently, academic research on human rights, and development practitioners have noted how ‘gender-restrictive groups are succeeding at using the language and legal tools of the human rights framework to present their anti-rights efforts as right-affirming initiatives’.

Significant efforts have been made to understand how these gender backlash narratives are built, such as research on forms of resistance and backlash, co-option, discourse capture and more. One such narrative tool to build gender backlash is when anti-gender-rights actors create a false narrative showcasing one community’s rights as being detrimental to another’s. This constructed narrative of a competition between the rights of two marginalised communities limits the frame of discourse to these communities, thus protecting existing power hierarchies.

This blog is based on original research for the dissertation for my M.A Gender and Development degree at the Institute of Development Studies. My work, since then, with Young People for Politics, Rejuvenate, and CREA has also been instrumental in writing this blog. In the paragraphs below, I expand on the role of ‘competition of rights’ in serving gender backlash agendas. Here is what I’ve found:

How is the narrative of ‘competing rights’ staged?

Rehana Fathima, a feminist activist from Kerala, India, uploaded a video of her children drawing on her naked upper body as a political act against sexualising women’s bodies, calling for action to reinterpret female bodies. My research on this ‘political act’, and responses to it by the State and other institutions, illustrate the ways in which her feminist gesture was eclipsed by a discourse on child safety.

In encouraging her children to draw on her naked upper body, Fathima was seen to be forwarding her own political agenda at their expense; she was accused of ‘sexual abuse’. My study revealed ‘censure’ from sites of legitimate authority, and ‘discourse capture’ were tools used to stage this competition between Fathima’s right to gender justice and her children’s right to safety.

These trends are seen globally; a more recent example is the trans-exclusionary stance promoted by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women (SR VAW). In November 2022 the SR VAW urged the Members of Scottish Parliament in a public letter to reconsider the Scottish Gender Recognition Reform Bill (GRR), which proposed simplifying the process of gender self-identification for trans persons. The SR VAW argued that the proposed reform provides an opportunity for perpetrators of violence to identify as women and access women-only safe spaces, thus risking further perpetration of violence against already vulnerable cis women.

In both cases, the accusations are not supported by any evidence, but are taken as legitimate concerns due to the authority of the inquirer. This narrative creates a false co-relation between the advancement of rights of one group with risks faced by another. It twists and repurposes the narrative shifting focus from the original cause – in Fathima’s case desexualising female bodies, and in the case of the Scottish GRR self- identification for trans persons– allowing for discourse capture. Additionally, backlash actors form intentional alliances to ensure cohesive action leading to this form of discourse capture. In instances where such overt alliances are not formed, such as in Fathima’s case, there continues to be cohesion across backlash actors because the narrative is built on gender norms coded into the socio-cultural, political, and economic institutions.

In the competition of rights, anti-gender-rights activists identify one group as ‘in need of protection’ and create a moral panic. Fathima’s children were assumed to be incapable of understanding the political act they helped create. Hence, none of the stakeholders engaged with the children to assess if they had consented to participating in Fathima’s political act, which is a valid concern with regards to upholding the children’s rights. In case of the SR VAW, the letter had the support of multiple trans exclusionary feminist and women’s rights groups. The SR VAW decided to represent their concerns, while disregarding the many representations made by feminist collectives who support self-identification for trans persons and oppose the arbitrary correlation between right to gender self-identification and increased risk of violence against cis women. Through this form of narrative building one group is identified as more vulnerable (i.e., children and women respectively in the above cases) and as having homogenous needs. Their rights are considered to be more valuable than those of persons belonging to less normative groups. This narrative of competing rights separates groups into neat boxes, ignoring the many intersections and critical ally-ship across marginalised groups and communities.

Piercing the smokescreen of competing rights

This form of narrative backlash not only disrupts progressive gender rights agendas but is built on and promotes existing gender normative and oppressive structures. While creating counter-narratives is essential, it is also critical to proactively build popular narratives that delegitimise, or create an adverse environment for, the work of backlash actors. Here are four recommendations:

- Human rights are indivisible: Rights are inseparable by nature and the rights of one community cannot be upheld by denying the rights of another.

- Nothing for us without us: All gender-rights discourses must ensure deep representation from the communities of rights holders themselves. Diversity and dynamism in representation is essential to counter backlash.

- Gender is never binary: Discourse on gender rights and development initiatives for gender-based rights must consciously include agendas that challenge gender binaries and represent non-normative forms of thought and action; it must not be depoliticised

- Be an ally –step up and/ or make space: Rights movements cannot exist in silos; therefore cross movement ally-ship is an important aspect of countering gender backlash. Gender rights are intrinsically linked to all human rights. We must learn to step up and give up our space in support of each other across movements.

5 ways Lebanon can #EmbraceEquity

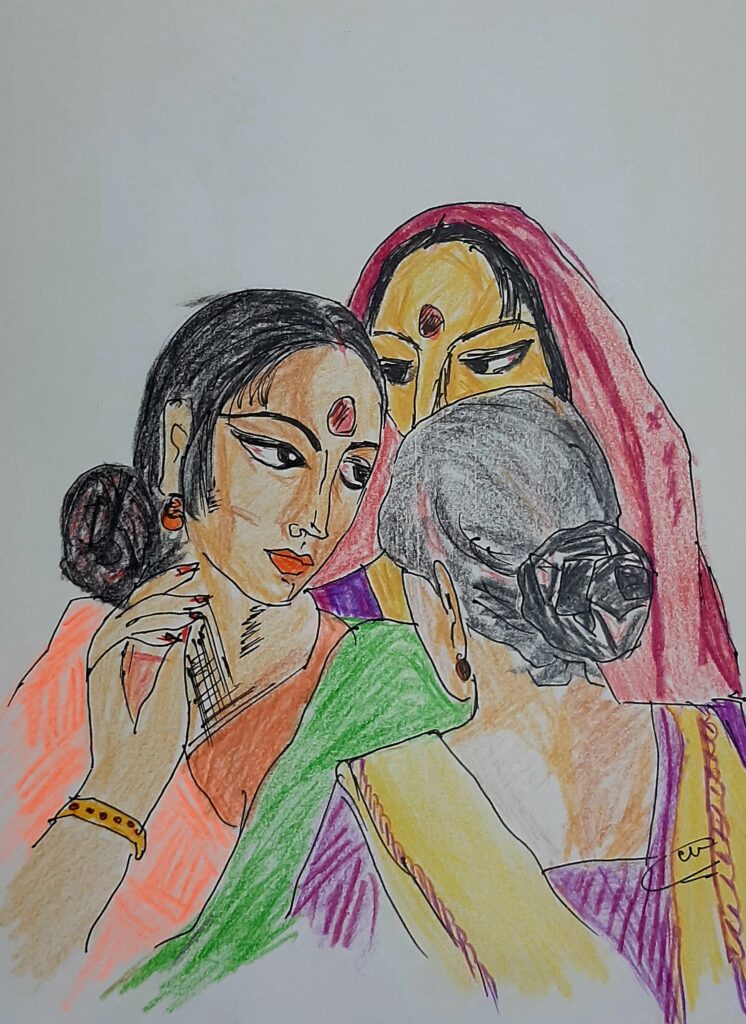

Gender backlash against women’s rights in Lebanon persists despite progress made by activists over the past few decades. Backlash in the Lebanese context continuously oppresses women’s rights, rather than being a reaction to progress.

This can take a broad range of forms such as structural discrimination and exclusion, all of which are fed, incubated and fuelled by the sectarian system. These forms not only fight and obstruct advocacy for women’s rights, but more importantly, impede the possibility of progress.

The perpetual and overlapping economic and political crises overtaking the country and the resultant blocked policy spaces since 2019 indicate that there is still a lot of progress to be made. With this in mind, here are five ways Lebanon can better #EmbraceEquity:

1. Lebanon must adopt a personal status law

Due to the absence of a civil code governing personal status matters like marriage, inheritance, and child custody, Lebanon depends on 15 distinct religious laws and courts for the country’s 18 acknowledged sects. Consequently, individuals experience different treatment based on their sex and sect, which results in discrepancies in women’s rights between sects. Under this system, women also do not have the same rights as men in the same sect.

By relegating family and personal matters to religious courts and abstaining from establishing civil courts, the state renounced its constitutional right (and obligation) to institute a civil family law. A unified personal status law needs to be adopted, specifically one based on equality between men and women.

2. Lebanon must amend its domestic violence law

In 2014, following years of feminist lobbying, the Lebanese parliament passed a domestic violence law, rigged with gaps. The law failed to criminalise marital rape and excluded former partners and relationships outside legally recognised frameworks from its protection provisions. Amendments in 2020 allowed for prosecuting not only abusive spouses but former spouses as well. The amendments also expanded the scope of ‘family’ to include current or former spouses, and extended the definition of violence to include emotional, psychological, and economic violence. Despite these improvements, gaps remain in the law and its implementation.

Domestic violence cases are usually investigated by police officers with no training in handling abuse cases, which needs a specialised and trained domestic violence unit. Additionally, while religious courts cannot interfere with civil courts’ domestic violence rulings, these can still rule in divorce and custody matters. Due to these circumstances, there is a growing need for a unified personal status law.

3. The Lebanese Labour Law must include domestic and agricultural workers

The Lebanese Labour Law fails to protect women’s rights in all respects, particularly those in domestic work. It excludes migrant domestic workers from its protections, leaving them vulnerable to the kafala (sponsorship) system that ties their residency to their sponsor, often leading to violations of their rights. Despite numerous reports of abuse in the past decade, there have been no significant official efforts to protect domestic workers. Without regulatory laws or monitoring mechanisms in place, there is little accountability for those who violate their rights.

The labour law needs to be amended to include migrant domestic workers, and the standard unified labour law should be upgraded and implemented. Migrant domestic workers should be allowed to unionise, and their rights should be protected. The law also excludes agricultural workers, primarily women, from social security benefits. Reforms are needed to protect these workers and to enhance equal opportunity and pay in employment between women and men.

4. The Lebanese Nationality Law must be amended

The Lebanese Nationality Law discriminates against women by preventing them from passing their citizenship to their children, explicitly stating that Lebanese citizenship is only granted to those ‘born of a Lebanese father.’ Although the government has taken some steps to ease the residency of children of Lebanese mothers, such as exemptions from work permits, demands for women’s right to grant citizenship to their children are still largely ignored.

While there have been some attempts to amend the law, the latest draft failed to reflect a commitment to equality, denying the children of Lebanese mothers from nationality, political rights, and some labour and property rights upon reaching legal age. The Lebanese nationality law should be amended to include every person ‘born to a Lebanese mother’.

5. Lebanese law must address violence against women in politics

The World Bank’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Index report ranks Lebanon 150th out of 156 countries in the category of Political Empowerment. Women’s underrepresentation in political decision-making limits their ability to shape the country’s direction. Successive Lebanese governments have failed to address the gender gap in politics, especially by resisting the implementation of a parliamentary quota. Further, women in politics are subjected to cyberbullying, defamation, and discrimination in the media.

Lebanon needs legislation addressing violence against women in politics, including instances of violence occurring within the political and public sphere, with the aim of outlawing all forms of violence against women in politics and promoting greater awareness among the public.

Looking ahead

Women in Lebanon face many challenges in their struggle for gender equality, as any attempts to address these structural inequalities are often faced with resistance from the people that benefit from the patriarchal and sectarian political system in Lebanon.

The ongoing struggles of women in Lebanon are a reminder of the importance of continued efforts to promote gender equality worldwide. We must #EmbraceEquity!

5 ways Uganda can #EmbraceEquity

The late 1980s was a turning point for gender justice in Uganda. The country reaffirmed gender-positive policies by embracing Affirmative Action in 1986, and incorporating Article 32 in the country’s Constitution in 1995. The article mainly addresses groups marginalised because of their gender and the historical norms that affect specific groups.

Uganda has seen many women join leadership positions both at the political and organisational levels. For instance, in the 2021 national election, 122 Members of Parliament were elected on their affirmative action positions. The affirmative action policies from the Parliament through other institutions have led to school girls from disadvantaged backgrounds accessing higher education.

Despite this progress, there has been significant pushback on the gender progress made by women’s rights organisations, women’s movement, women human rights defenders (WHRD), and feminists in Uganda. This is because the power being held by women in leadership positions is not reflected in the policies and laws passed by Parliament.

Gender backlash is happening in digital spaces and moving into offline spaces. Even though the advancement in technology comes with its advantages, it opens up women and girls using technology to online backlash, in a context where the regulation and implementation of policy to protect them from online gender-based violence is lacking. Countering Backlash partner WOUGNET is working to counter this.

For International Women’s Day 2023, we share five ways Uganda can promote gender justice within the region to better #EmbraceEquity.

1. Embrace a rights based approach to gender-justice

Some of the religious institutions in Uganda denounce gender-diverse rights, such as same-sex marriage. The globalising world intersecting with local traditions is producing unexpected ways of thinking about rights.

Religious and cultural groups command a huge following and often oppose equal rights for LGBTQI+ people, sex workers, and feminist movements, especially those that challenge the mainstream gender norms. They form and inform tactics for opposition, and intentionally hinder opportunities for WHRDs, LGBTQI+ people, and sex-worker communities to advocate for their rights, occupy public space and become a part of democratic processes. Religious institutions must encourage new understandings of gender-diverse rights and how to secure them in Uganda.

2. Stop violence against feminist activists and human rights defenders

The existence of different methods of violence against feminist activists, human rights defenders, and sexual rights advocates continues to evolve and manifest differently in spaces (online and offline). These attacks are through words, phrases, images and representations of women in media, where feminism is framed as the main cause of women’s problems. The raiding of LGBTQI+ shelters, the killings of LGBTQI+, and protests against same-sex marriage are a combination of direct and visible attacks on activists.

The government must stop shrinking aid programmes using the Non-Governmental Organisations Act and Anti-Money Laundering Act. They should also make funding available to research the forms and types of violent attacks happening online and offline, and include methods for public awareness on how backlash can impact women’s rights and progress on gender justice that can affect Uganda’s socio-economic development.

3. End digital and online attacks

Advances in the use of technology and digital platforms have a flip-side: the same technologies are used as tools to share masculine narratives and to attack gender advocates, feminists, and sexual rights advocates. They are used to push back gender equality achievements such as women political candidates losing seats in Parliament, for instance, the former Member of Parliament Sylvia Rwabwogo case of cyber harassment worsened by biased media reporting led to Rwabwogo’s loss of a seat in the next Parliament.

The internet can enable and also promote unwanted male gaze which causes intrusion of women’s privacy online and offline hence affecting women in public spaces. There have been increased regulation of online spaces using existing laws such as the Computer Misuse (Amendment) Act 2022 and the Uganda Communications Act 2013. The latter has been used by the government to disrupt and shut down the internet, restricting individual expression online. Internet shutdowns worsen the inequality and injustice women already suffer.

Gender activists are progressing in bridging gender inequalities, reproductive rights, and freedom from gender-based violence. However, access and use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) can help to bridge the gaps or deepen the gaps every time the internet is shut down or blocked.

There needs to be more training on network measurement in order to quantify and qualify the impact of internet shutdowns on gender justice and women’s rights online.

4. Support civic space

Civic space in Uganda is shrinking. There has been government interference and threats to close some civil society organisations, including many prominent organisations working to promote gender justice. In February 2023, Trade Minister David Bahati cited about 30 non-governmental organisations alleged to be involved in the promotion of homosexuality in Uganda that will be investigated. He added that the list of NGOs will soon be submitted to relevant security bodies for formal investigations into their activities with a view to closing their operations in Uganda. The anti-homosexuality bill will be introduced to the Parliament of Uganda to target people wishing to engage in homosexual acts, as well as organisations working on LGBTQI+ rights in the country.

In the past, women-led civil society organisations that are working with structurally silenced women such as lesbians and sex workers expressed facing challenges in their advocacy work because they are generally considered groups that are working with people engaged in criminal and immoral activities.

We must work with and build the capacity of the key stakeholders such as policymakers, journalists, and the media on the impact of shrinking civic space and gender-restrictive attitudes and discourses.

5. Support organisations fighting for gender justice in Uganda

There are local organisations, groups or people who are doing important and exciting work in Uganda related to the issues. This type of work is significant for the fight against gender backlash in Uganda, and must be supported.

Looking ahead

Although there is significant backlash against gender rights at the moment in the country, there are also opportunities to create a gender-just Uganda. We must work together to #EmbraceEquity.

Backlash against student activists during #MeToo in Kolkata, India

Student politics in Kolkata is dominated by left-leaning organisations who look at the world in terms of ‘class struggle’ and claim to be supportive of all democratic movements – including women’s movements and anti-caste struggles. However, some scholars such as Arundhati Roy have critiqued this claim, arguing that social equity does not always extend to caste.

Kolkata’s female students faced caste and gender backlash during the #MeToo movement. This blog explores how this backlash operates against female students in Kolkata’s public universities during the #MeToo movement, from my recently published paper ‘Caste and gender backlash: A study of the #MeToo movement in tertiary education in Kolkata, India‘ . Here is what I found.

#MeToo and Anti-caste

There is a strong anti-caste critique of the #MeToo movement in India argued by Dalit- Bahujan- Adivasi (DBA) feminists. It manifests in gaps of the Indian feminist movement and with female student activists belonging to the two social identities in the universities.

In my recently published paper, I show that politically left-leaning (or ‘Leftist’) male-dominated political organisations in Kolkata’s university campuses use these gaps to their advantage as tools of gender backlash. They uphold established power structures on campuses, silencing and removing both categories of women – DBA and Savarna – from spaces of power and quashing their #MeToo incidents and demands for redressal.

The #MeToo movement led to these institutions strengthening and developing the proper functioning of the universities’ Internal Complaints Committee (ICC), the formation of Gender Sensitisation Committees against Sexual Harassment (GSCASH), and stronger redressal bodies on campuses and in political organisations.

But even with these committees, my research shows that female students continue to constantly receive backlash when sharing their #MeToo posts on social media, calling out perpetrators in general body meetings and demanding justice.

How caste and class are used as tools of gender backlash

Backlash to gender equality can be viewed through two broad approaches. The first is as an immediate reaction to progressive change made or demanded by women. The second is inherent discrimination in power structures that affect women’s experiences of backlash differently. My research uses both of these approaches to explore gender backlash.

Two clear themes emerged from my interviews with female student activists belonging to both DBA and Savarna groups. These were the centrality of power and misogyny, and how they operate together to create gender backlash. All the respondents said that the powerful positions in the Leftist political organisations on campuses were held by Savarna men, although the organisations were by principle pro-working class. Issues of sexual harassment and gender sensitisation were most often avoided by bringing up the caste and class of female party members whenever men felt that their power was being challenged.

Respondents described how the leaders of political parties they worked in insisted that they were elite middle-class women and that issues such as calling out perpetrators of sexual harassment online and in general body meetings were middle-class issues and actually did nothing for DBA women.

When I described my experience with the harasser, he confidently dismissed the allegation and retorted with accusing me and other Savarna female members of planning to form a group to falsely accuse men in the party of sexual harassment, malign the party’s image and beat up the men. He kept repeating that urban elite feminists like us do nothing constructive for the women’s movement and marginalised women.

This type of backlash silenced Savarna feminists and did nothing to serve the interests of DBA feminists on campuses. It ultimately removed the crucial need to address sexual harassment from their political activities.

Respondents repeatedly emphasised that Leftist organisations in the universities tend to integrate caste within class, and target their position in society to reverse any attempt to address critical issues like sexual harassment. Being upper caste (and, according to the male leaders, automatically upper class), the groups first need to address the issues of the working class and then gender.

Intimidation through threats of physical and sexual violence and marginalisation using the position of caste and class in society creates effective backlash against upper-caste female students, ultimately silencing them and stalling any progressive change. Dalit respondents mentioned that Savarna women are pitted against Dalit women strategically by Savarna male leaders. Similarly, Savarna women are pitted against Savarna women within the party which is also a subtle form of backlash.

Bridging the rift

The purpose of this study using conventional and alternate conceptual approaches to backlash was to reveal that they can be understood in unison in this case and might also be relevant in understanding and further analysing backlash.

The intersection of gender identity and the position of caste and class in society plays a crucial role in generating gender backlash. Feminist movements must include an analysis of caste and class to understand the needs and aspirations of women belonging to DBA and upper-caste backgrounds. Anti-caste and anti-class movements need to examine patriarchy and sexism[19] [20] within their movements.

Both movements should focus on the actual life situations and experiences of women. Concepts of gender backlash that focus on power, and why and how backlash occurs, should also look at the intersection of gender identity and the position of caste and class in society to better understand different groups’ experiences. Concepts of backlash focusing on intersectionality should look at how power is exercised to generate gender backlash. This combined understanding will contribute to strategies for dealing with backlash and make efforts to mitigate it through activism.

We must bridge the rift between Dalit and Savarna feminists and be inclusive. Only then can the valid narratives emerging within the two different groups of feminists which generate gender backlash come to a stop.

Grasping Patriarchal Backlash: A Brief for Smarter Countermoves

Nearly three decades ago the UN World Conference on Women at Beijing appeared to be uniting the international community around the most progressive platform for women’s rights in history. Instead of steady advancement, we have seen uneven progress, backsliding, co-option, and a recent rising tide of patriarchal backlash. […]

Caste and Gender Backlash: A Study of the #MeToo Movement in Tertiary Education in Kolkata, India

In the light of the #MeToo movement, this paper explores how the positionality (in terms of caste and class) of female university students in Kolkata, India is employed as an instrument of backlash to pushback their efforts at making progressive change with regard to sexual harassment. […]

Empty promises: Continuing the fight for trans rights in India

Despite a rich cultural tradition of gender-fluidity, the transgender community in India have been stigmatised as a ‘criminal tribe’ through a colonial-era law. The community has struggled for their rights over decades, and only after significant engagement with the judiciary were they finally counted in the population Census of 2011.

It wasn’t until findings of an Expert Committee in 2013 into the discrimination of the transgender community that there was significant legal change. After a Public Interest Litigation, the Supreme Court of India ruled that transgender persons had the right to self-identify as male, female or a third gender. It also brought into law that the constitutional rights to life, dignity and autonomy would include the right to a person’s gender identity and sexual orientation. The government then brought in the ‘Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019 (TG Act)’, and issued the Rules in September 2020, which are used to enforce the act.

But the transgender community has seen little change, and still face discrimination in everyday life.

“The teacher said to my father, ‘Take your son away, keep him somewhere else, I cannot teach him in school. Only if he behaves properly, I’ll be able to teach him in school’. I tried really hard but I was never able to behave ‘properly’. … my walk was different; my voice was different…”

The poster reads: “‘You shouldn’t come looking like this, You shouldn’t walk around like this, You should walk like a boy.’ This is how I would be thrown out of school.” A representative of the transgender community. Why does this injustice continue in Education despite the guarantees in the Transgender (Protection of Rights) Act 2019 and the Rules (2020)?” Credit: Centre for Health and Social Justice.

Discrimination remains

The TG Act and Rules have many provisions, including a simpler process for self-identification, setting up a Welfare Board and a Transgender Protection Cell, and creating separate infrastructure in hospitals, jails, shelter homes, as well as separate washrooms everywhere, yet none of this has been implemented.

“Despite the reading down of Section 377 or the passing of the Transgender (Protection of Rights) Act 2019, we have not received any opportunities or benefits that have been promised to us in law.

The only change is that in forms and documents there’s been the addition of the word “Others” or “Transgender” but these terms really have no benefit for us.”

The disregard of the mandatory Equal Opportunity policy in all establishments leads to continued discrimination against the community in all social settings, including families, neighbourhoods, educational institutions, public places and limits opportunities to find employment. Many in the transgender community have not had access to schooling, and are not able to read the TG Act and know what their legal rights are.

“When we approach the police, their response is, ‘Wait outside; do you expect us to listen to you right away? Are you going to give us instructions?’”

Demanding action for trans rights

The Centre for Health and Social Justice (CHSJ) (partners of Countering Backlash) and the transgender collective Kolkata Rista, led an event in July, sharing findings from a recent scoping study they conducted. The event brought together members of the transgender community along with senior officials from the police department, the health and AIDS Control department, and correctional facilities, to showcase three short films and posters which highlight the discrimination transgender people face in education, healthcare, work, and from the police.

The event started the creation of a support system for the transgender community with the institutions that attended, who must use their power to enact positive social change. Kolkata Rista also launched a community crisis response and support cell with a helpline which will respond to any incident of violence or harassment and discrimination faced by the transgender community in Kolkata. It will include a safe space for shelter and medication or counselling.

The scoping study carried out by CHSJ with people in the transgender community brought out the lack of meaningful change in their situation despite their aspirations for self-improvement. The study also found that key people in the police department, health department and HIV/AIDS prevention programmes who have the power and knowledge to enact change have not yet carried out training for their staff on the TG Act of 2019 and the Rules.

Watching the stories of their own lives and struggles unfold in the films was an emotional experience for the community members. They shared painful experiences of rejection and humiliation and how a lack of opportunities to make changes in their lives affected them. The police officials and those leading AIDS programmes pledged that they would do more to provide meaningful support after watching these films and hearing their stories.

Now, those words must become action, and we must keep a vigilant eye on progress to make sure that rights are realised.