This year, millions of people in South Asia head to the polls. Potential outcomes of elections in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, however, do not bode well for women’s rights or gender equality, says Countering Backlash researcher, Sohela Nazneen. The road ahead is difficult for women’s and LGBTQ+ struggles, as autocratic leaders consolidate power, and right-wing populists, digital repression, and violence against women and sexual minorities are all on the rise

Repression of civic space

CIVICUS is a global alliance of civil society organisations that aims to strengthen citizen action. After the Bangladesh government’s repression of opposition politicians and independent critics in the run-up to the country’s January elections, CIVICUS downgraded Bangladesh’s civic space, rating it as ‘closed’. India and Pakistan it ranked as ‘repressed’.

All three countries recently passed cybersecurity laws and foreign funding regulations that obstruct women’s rights, and feminist and LGBTQ+ organising. In Bangladesh, the ruling Awami League – in power since 2008 – boycotted by the main opposition party during the most recent elections. In India, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), in power since 2014, has systematically undermined democratic institutions and built a Hindu-nationalist base. Pakistan has experienced multiple military forays into elections and politics that effectively limited competition between parties.

When it comes to gender equality concerns, however, these three South Asian countries feature contradictory trends. All have, or had, powerful women heads of government. Former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, and current PM Sheikh Hasina have led Bangladesh; in Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto governed from 1993–1996. Indira Gandhi governed India from 1966 to 1977, and there have been many other regional party heads. During this period, things have improved for ordinary women. Women live longer, more women receive greater education, and they are increasingly active and visible in the economy.

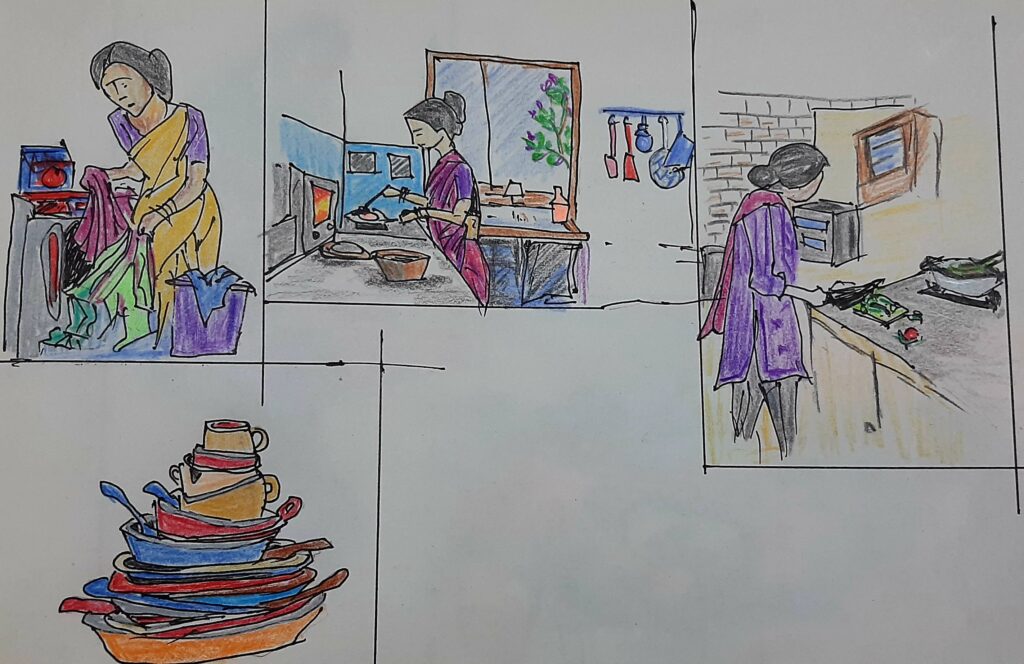

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have all been governed by women leaders. But these countries still experience strong pushback against women’s rights from conservative forces

But persistent gender inequalities remain. Violence against women in public places and within the home is high. Women’s sexuality is subject to heavy policing, and there is strong pushback against women’s rights and gender equality from conservative right-wing-populist forces.

At the Institute of Development Studies, we have been tracking backlash and rollback on rights in the region through two programmes: Sustaining Power and Countering Backlash. Our exploration of the links between a rollback in women’s rights and autocratisation shows specific manifestations of gender backlash.

Bodies as battlegrounds: direct assaults and hollowing-out policies

Women’s bodies have always been policed, and the rights of sexual minorities are highly contested in South Asia. Recent years have seen an increase in direct assaults against feminist and LGBTQ+ activists in online and physical spaces. In all three countries, right-wing political parties and religious groups have mobilised a strong anti-rights rhetoric to oppose critical women’ rights, feminists, and LGBTQ+ activists.

But the battle over women’s bodies is also visible in policymaking. In Bangladesh, for example, sexual and reproductive health, previously framed in terms of rights, have become more technical. In 2011, the government introduced a National Women’s Development Policy, which gave women equal control over acquired property. But mass protests by Islamist groups claiming this clause violated Shariah laws forced the government to backtrack.

Islamist protests against a proposed new policy giving women equal control over acquired property forced the government to backtrack

Women’s rights groups lost their relevance to the ruling elites as the country shifted towards a dominant party state and their support was not needed keep the elites in power. These elites now seek to contain opposition from religious and conservative political groups, whose support is crucial to remain in power. To consolidate its power, the authoritarian Awami League – one of the biggest parties in Bangladesh – needs to appease conservative forces. This limits the avenues for feminist activists to engage in policy spaces, as they have done since Bangladesh’s democratic transition in 1991.

State patronage, gender, and de-democratisation

The pushback against gender equality is not limited to sexuality or the policing of women’s bodies. Populist right-wing political parties have framed women’s economic empowerment in ways that promote the traditional role of women as carers and nurturers, in line with conservative cultural traditions.

Populist right-wingers frame women’s economic empowerment in ways that promote their traditional role as carers and nurturers

In India, the Modi government rolled out various development schemes targeting women. These included free stoves and natural gas cylinders for women, and maternity benefit schemes. Of course, these succeeded in attracting the female vote – but they also helped tie women to their traditional social roles. India heads to the polls in April and May. Election fever is intensifying. At the same time, the BJP’s paternalistic empowerment rhetoric is focusing increasingly on the role of women as nation builders.

In Bangladesh, women workers dominate the country’s main foreign exchange earning industry: ready-made garments. Before the elections, garment workers were engaged in negotiations demanding higher wages. When negotiations failed, police made violent clampdowns on the resulting protests. To consolidate its power in a hotly contested election, the ruling Awami League chose to back the garment factory owners, who hold a majority in parliament.

Protests, politics and repression

The introduction of cybersecurity laws and tightened regulations over NGO funding leave limited space for dissent. Activists and rights-based organisations risk fines, arrests, imprisonment, judicial and online harassment.

Nevertheless, we are still seeing a surge in women-led protests and feminist and LGBTQ+ activism. Protesters are using innovative strategies that disrupt everyday order. These include roadblocks, sit-ins, and theatre performance, graffiti, poetry, and songs to reclaim notions of citizenship and national belonging. The Aurat March is a feminist collective that organises annual International Women’s Day rallies to protest misogyny in Pakistan. Last year, it captured the imagination of a new generation to dream of a more equitable society.

In 2019–2020, Indians rose up against proposed amendments to the Citizenship Act that would offer an accelerated path to citizenship for non-Muslims. The Shaheen Bagh protests, led by Muslim women, saw diverse groups coming together to reclaim the notion of a secular India. Anti-rape protests in Bangladesh led by young feminist groups drew attention to archaic laws, and demanded safety for all types of bodies and genders. These are only a few examples. Yet despite their effort to reclaim public spaces, activists had no sustainable effect on countering state power.

These protests are vital spaces in which citizens can begin to imagine different kinds of polity, and to cherish ideals of democracy. They also help to re-examine intersectional fault lines within protest movements, and find new forms of solidarity.

This article was first published on ECPR’s political science blog site, The Loop.