Feminist activism and organising for gender justice are rapidly evolving. We are seeing new energies and new ways of building a feminist future. This is happening in a time of multiple and interconnected crises, adversely impacting women’s, trans folk’s and non-binary people’s rights, as well as gender equality gains made in policy, discourse and practice.

To explore the challenges to feminist and gender justice activism and to identify new energies in the field, Sohela Nazneen and Awino Okech were invited to guest edit the Gender & Development journal’s special double issue on Feminist protests and politics in a world of crisis. You can also watch the authors discuss their articles in an Institute of Development Studies’s webinar held in November 2021.

Why now?

Feminist activism has faced new and diverse challenges over the past decade. The rise of conservative and populist forces, the growth of authoritarianism, racism and xenophobia, and austerity in many countries are just some of these challenges. These have led to an increased dismantling of civil liberties, freedom of speech, expression and peaceful assembly.

Across the globe, feminist and gender justice activists are recalibrating their actions to face these challenges.

From Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and climate justice activism, we are witnessing a growth of transnational and intergenerational organising. Feminist and gender activists are seizing the moment to reimagine democracy, gender and power relations, and humanity.

Feminist activism requires presence across policy, online spaces and the street…

What we explore

In this special double issue on Feminist protests and politics in a world of crisis, we set out to answer two central questions:

- How are movements sustaining thriving, robust and resilient spaces and alliances in a world of multiple crises?

- How is politics of solidarity created at the national and trans-national levels?

To answer these, we explore varying themes and collective mobilisations for feminist and gender justice actors through 20 articles from different regions of the world. Below are some examples of what you will find:

Nothing is as it seems: ‘discourse capture’ and backlash politics; Tessa Lewin

Tessa Lewin develops the concept of discourse capture, analysing how gender equality is undermined by right-wing political parties and women’s groups as they co-opt progressive feminist agendas. Tessa details examples from around the world, including the US pro-life movement, the ‘Vote No’ campaign in the Republic of Ireland, the ‘Anti-Homosexuality Bill’ in Uganda, and more.

Femonationalism and anti-gender backlash: the instrumental use of gender equality in the nationalist discourse of the Fratelli d’Italia party; Daria Collela

Daria Collela explores the media strategies of right-wing political parties in Italy, and how they frame people of colour, especially those of a Muslim background, as perpetrators of violence against women. Daria argues that these nationalist forces use gender equality agendas to bring together a diverse set of actors to promote racism, anti-migrant agendas and xenophobia.

The resistance strikes back: Women’s protest strategies against backlash in India; Deepta Chopra

Deepta Chopra analyses the strategies used by Muslim-women activists in Shaheen Bagh, Delhi, India. These women led a four-month-long sit-in protest against the police violence inflicted on student activists and India’s discriminatory citizenship laws. Deepta details how the grandmothers of Shaheen Bagh used inclusive frames for claiming citizenship, rotated care work duties with younger women of the community so the latter could participate, and how the performance of poetry and songs transformed the Shaheen Bagh as a space for building cross-sectional solidarity.

Visible outside, invisible inside: the power of patriarchy on female protest leaders in conflict and violence-affected settings; Miguel Loureiro and Jalila Haider

Miguel Loureiro and Jalila Haider examine the Hazara women’s protests in Balochistan, Pakistan. They look specifically at how the women went on hunger strike and drew national attention to the killing of and violence against the men of their community. Women’s participation transformed the movement from male-dominated violent protests to women-led peaceful ones. But despite women being the face of protests, they are still excluded from key decision-making structures, drawing attention to the slow pace of change.

Gendered social media to legal systems, online activism to funding systems

Other articles in this issue explore how South-South transnational solidarity is built. They examine the role of public performance, street protests and intergenerational dialogues in creating solidarity across diverse social groups and generations in the movements such as “A Rapist in Your Path” in Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Bolivia and the anti-abortion rights movement the Green Wave in Argentina. There is a focus on queer and feminist activism in online spaces in Nigeria (such as #ENDSARS), Lebanon, Brazil and how online engagements help to raise contentious issues but also pose a significant risk to activists. For many authors, how to sustain movements and protect spaces for autonomous organising remain key concerns. Several of them focus on the development of alternative funding mechanisms and influencing bilateral negotiations as key pathways for sustaining activism.

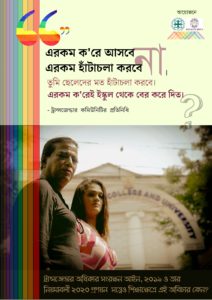

Further articles analyse how having a seat at the table in Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines, Argentina were important for making and sustaining pro gender equality policy change and explore the ways an active and effective feminist presence in policy political spaces can help to counter gender backlash.

The strength and determination documented in the articles of feminists and gender justice activists, gives us hope for a better, equitable, fairer future.